Understanding What eCycling Is, and What It Isn’t

It’s not uncommon for people to conflate the concept of recycling with the ideas of reusing or refurbishing items. They’re actually very different processes with equally different outcomes. In the realm of device lifecycle management, it’s important that schools understand the differences — particularly the distinction between recycling electronic waste and refurbishing or reusing it.

While the devices in question no longer meet educational needs or requirements, they might still be useful for other users. In such cases, a district’s best option might actually be reselling the devices, which can then be refurbished and resold.

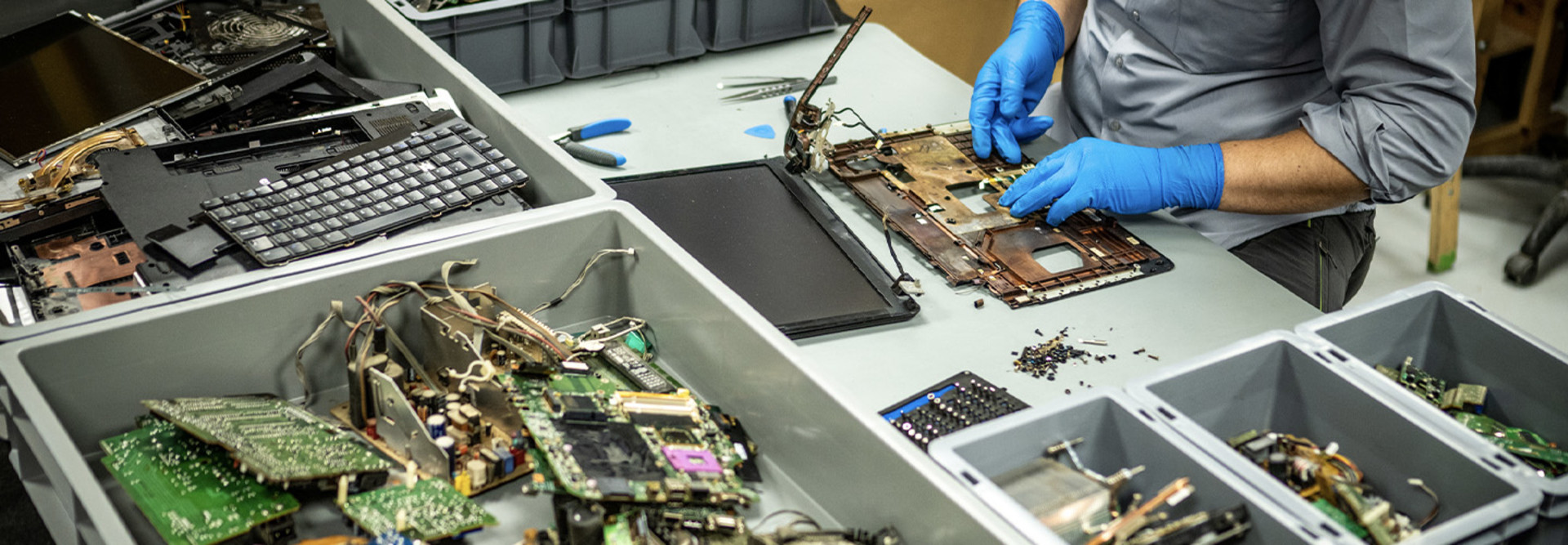

However, eCycling is something else entirely: “eCycling is the process of extracting valuable materials from these devices, so that they can be reused in new things, whether it be new electronics or other goods,” says Steve Schuldt, a business development executive at RePower, a company that helps organizations determine what to do with old tech devices and facilitates the process of refurbishing, reselling or recycling them.

Ultimately, Schuldt explains, eCycling will always be better than tossing a device in the trash. However, to get the maximum value out of a school’s technology investments and to avoid unnecessary waste, he says, eCycling should also be the last step in the device lifespan.

DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC: Manage all stages of the device lifecycle.

Putting eCycling into Practice at K–12 Schools

To anyone who’s ever witnessed a child using a tablet on an airplane or at a restaurant, it comes as no surprise that young users and device damage go hand-in-hand. Broken screens, stickers, unidentified sticky substances and bed bugs are just a few types of damage witnessed by Josh Kovacich, IT director at Buffalo Public Schools. Kovacich previously worked with the Niagara Falls School District when it was first issuing laptops to students. “It was a learning experience,” he recalls. “There was a lot of damage in the first year at that time.”

In Buffalo, the district had already developed and implemented its one-to-one device program when the pandemic hit, forcing the district to expand and fast-track the program, Kovacich says. Now, with devices initially purchased in 2020 gradually approaching end of life, the district is working to develop its overarching device lifecycle strategy, including whether and when it’s time to consider disposing of outdated devices.