Because the explosion rendered Minnehaha Academy’s north campus unusable, the district relocated its main data center and administrative hub to its south campus. Meanwhile, the school needed a temporary campus for additional space. Cummings said the district was fortunate to find a building with relatively modern infrastructure that had been vacated by Brown College two years earlier.

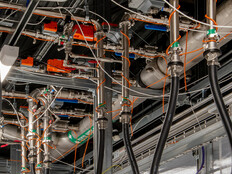

With a lot of helping hands, the new location was turned into a temporary high school in three weeks. The campus was transformed with an Aruba network that included 10 switches, 60 access points and a 20-gigabit fiber backbone; a VoIP phone system; overhead paging; interactive flat panels, projectors and other audiovisual technologies; a point-of-service system for the lunchroom; and security cameras and door access control systems.

Cummings said much of this was possible because the existing infrastructure in the vacated building had been well maintained. It was labeled, documented and well organized, making it easy for Minnehaha Academy to adapt the technology for its own purposes.

By 2019, the school’s original campus had been rebuilt with a focus on hybrid data centers and a move away from on-premises storage. The school also prioritized an ongoing move to cloud-based applications. Other networking technology in the new building included CAT 6A cabling, VMware servers, Aruba switches and access points, and external Wi-Fi.

DIVE DEEPER: Should K–12 schools invest in Backup as a Service?

Beaverton School District’s Road to Data Recovery

While Beaverton School District had to spend less time physically rebuilding its data centers, school leaders like Langford needed a way to solve for missing data, and he needed to do it quickly.

“It’s a million-dollar penalty if you don’t make payroll,” he said.

He and his team started by communicating the problem to the staff members. He remembers painful phone calls in which “it would have been easy to blame the technology.” Instead, he and the team owned up to their mistakes in not having correctly backed up the data.

Langford referred to the recovery process as a roller coaster. Celebrating even a small victory was often followed by a stomach-churning realization or new challenge. A heat-damaged backup tape sparked exaltation, only to be followed by despair as the district began building backups from scratch.

RELATED: Will bit rot destroy your district’s data?

One of the biggest breakthroughs, he said, came when the team discovered an employee had exported HR data. “He didn’t know they weren’t supposed to keep payroll PDFs on their desktop,” Langford said to audience laughter. “We had to say, ‘We’re super mad at you, but thank you so much.’”

Looking back on the disaster recovery process, Langford admitted there were times that he wanted to quit his job and walk away from the challenges. He stressed the importance of resiliency in leadership and communication with team members and school staff. “How are you going to react in a horrible moment of crisis?”

The session resonated with the full audience, who took notes, asked questions and approached the speakers after the session concluded. Both Langford and Cummings urged schools to have a disaster recovery plan that includes offsite backups and to check those backups regularly.

Join EdTech as we provide written coverage of CoSN2023. Bookmark this page and follow us on Twitter @EdTech_K12.