“We’ve moved coding down to the first grade,” says Land. “We now have programmers in elementary school teaching computer skills to older students and parents.”

None of this would be possible without a solid technology foundation. De Queen is improving its infrastructure and its network backbone as part of its upcoming one-to-one initiative, adds Land. In the meantime, younger students have access to Dell, Lenovo and Samsung Chromebooks in the classrooms, while older students can use Lenovo desktops in the computer lab. An Aerohive wireless network allows De Queen students to access Google Apps for Education.

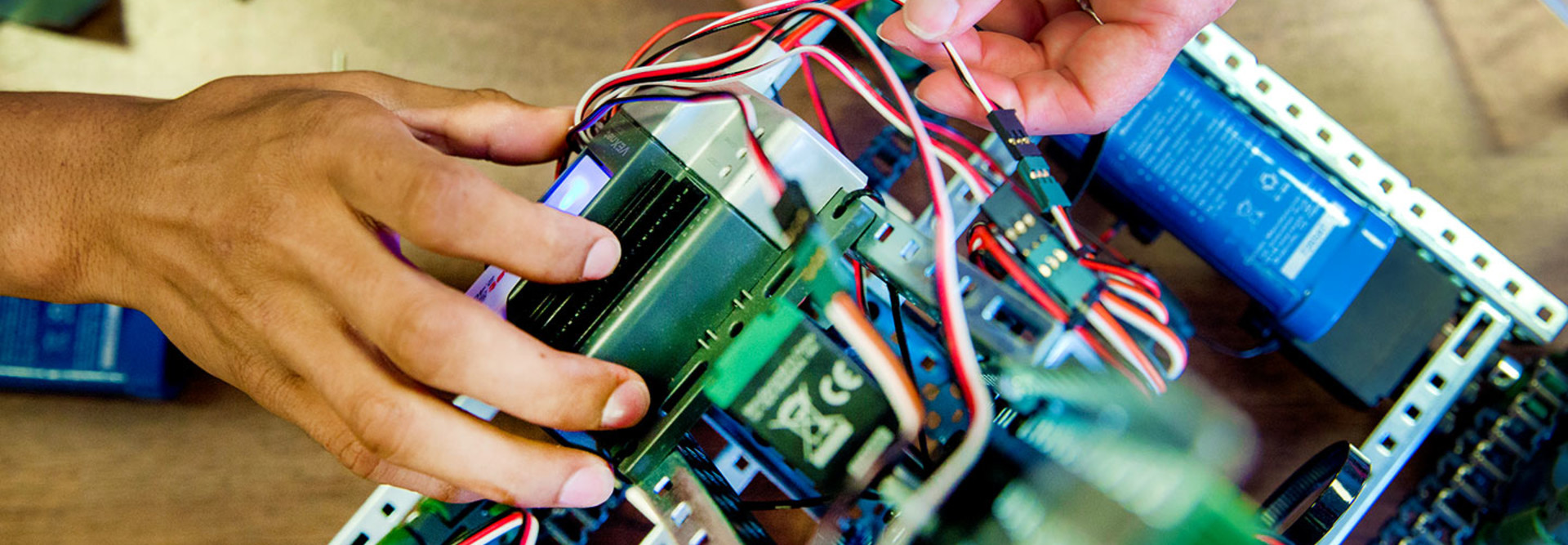

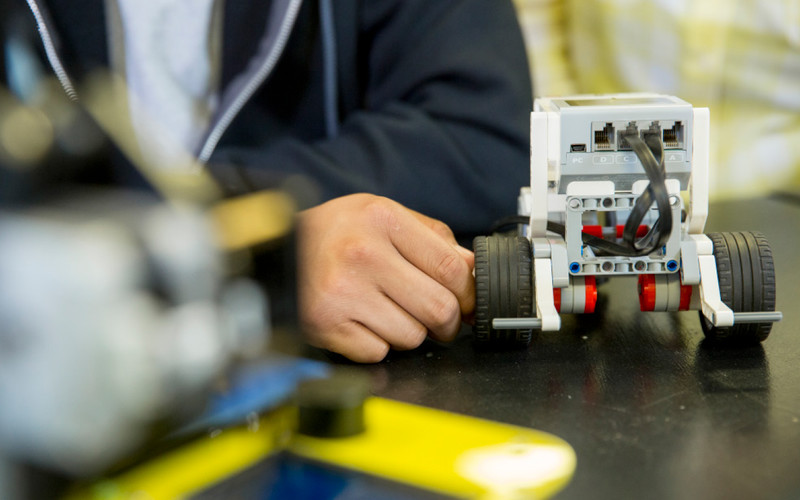

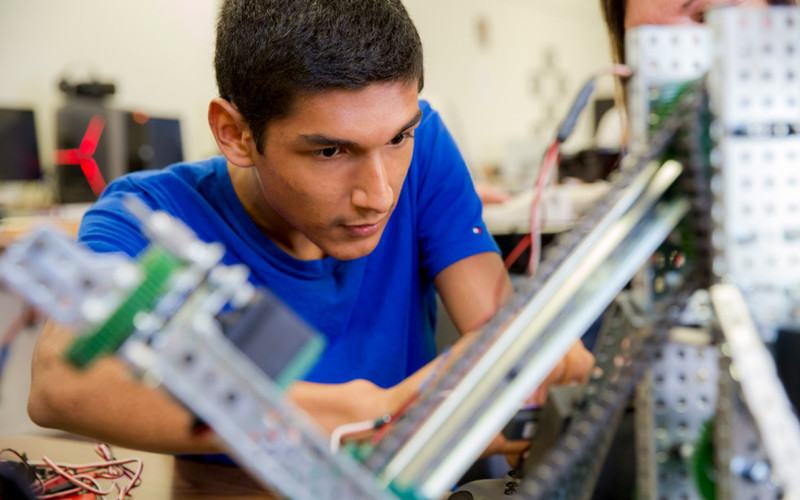

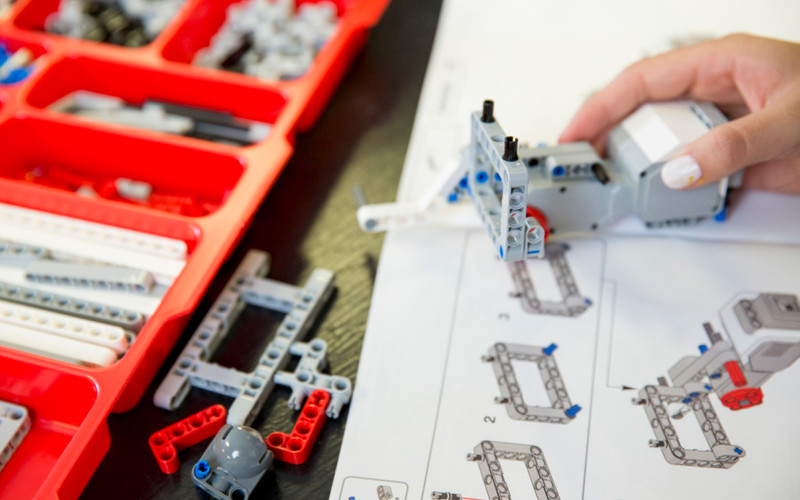

Offering hands-on STEM instruction energizes students in a way standard teaching techniques often do not, says Land. And it’s not just playtime for the kids; they have to be able to discuss each project and talk about how it benefits people in the real world.

“We’re teaching computational skills by having students break large problems into a sequence of smaller, more manageable ones,” Land says. “All the while, they’re having a great time learning how to make a robot turn or move inside a game.”

MORE FROM EDTECH: See how makerspaces can help K–12 students learn to code!

Hacking Classes Can Teach Students to Be Good Digital Citizens

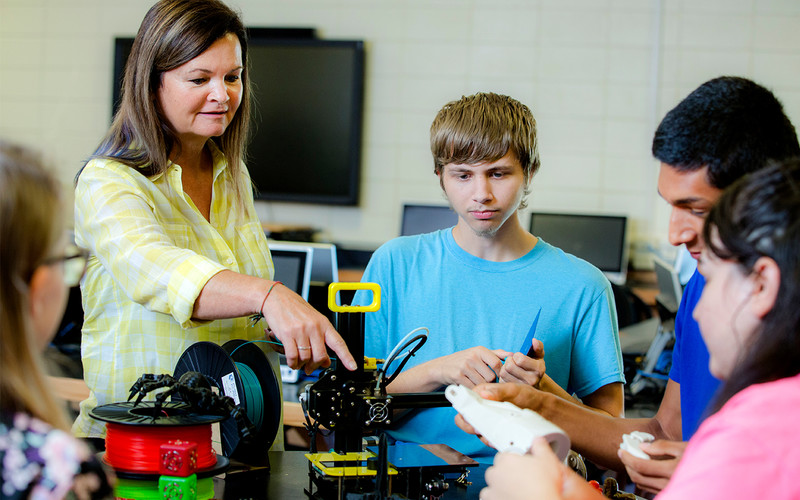

While Land’s students build their critical thinking skills, students in Illinois use their skills to solve real-world problems. For 26 hours last January, hackers took over Warren Township High School in Gurnee, Ill. But these weren’t bad guys trying to steal information; they were students taking part in a weekend hackathon called the Devil Hack, which drew participants from 11 high schools across Northeastern Illinois.

Their challenge: come up with creative ideas for increasing energy efficiency, improving health and enhancing society.

More than 150 students took part, and their creations were awe-inspiring, says Rico D’Amore, who was Warren Township’s director of educational technology for the past seven years before moving to a new job in September. For the past two years, D’Amore and high school activities director Kimberly Lobitz have run Devil Hack.

“These students come up with blow-your-mind ideas,” D’Amore says. Teams of students brainstormed devices, such as a smart mirror that has conversations with students to boost their self-esteem and a digital road sign that adjusts speed limits automatically based on weather and road conditions.

They mapped out apps that scan web content for keywords to flag potential bullying, and social media platforms that teachers could use to share ideas and connect with other educators. They devised energy-efficient lighting systems and dreamed up audio reminder apps that use artificial intelligence to gauge a user’s mood and adjust the tone accordingly.

“These students don’t need to be told, ‘Read these pages in your textbook and then discuss them.’ They need to be told, ‘Here’s a problem; use what you’ve learned to solve it,’ ” D’Amore says. “This is how teaching should evolve.”

With 4,200 students, Warren Township is one of the largest high schools in Illinois. Four years ago, it launched a one-to-one initiative using Dell Chromebooks, which rely on an Aruba wireless network for internet access. For the hackathon, the schools’ IT department set up a dedicated guest network inside the school’s gym, then took it down when the event was over.

While there isn’t a formalized coding class at Warren Township, the school sponsors an after-school club called the Tech Team, where students work on coding projects using tools like Scratch and Code.org.

The biggest challenge to pulling off the hackathon was persuading other educators that hacking isn’t always a bad thing, and that this problem-solving mindset is essential to STEM learning, D’Amore says. But once they see the kids in action, the enthusiasm is infectious, spreading from students to parents and even teachers, he says.

“People come up to me and say, ‘I wish I had this back in high school,’ ” he says. “Going to the hackathon has been one of the greatest times of my life.”

MORE FROM EDTECH: Read how K–12 schools are using hacking exercises to teach kids cybersecurity!

Successful STEM Classes Start with Big Ideas

At Davis School District in Farmington, Utah, thinking big is a must. With nearly 76,000 students spread across 62 elementary schools, 16 junior highs and 10 high schools, Davis is the second largest district in the state. Not surprisingly, Davis offers a diverse range of STEM events and programs for its students, says K–12 STEM director Tyson Grover.

Fourth- through sixth-graders can enter the STEM Olympiad and compete in six events, such as creating circuits using an Arduino kit or completing a digital puzzle using Scratch.

Junior high students can participate in the STEM Fair, which is like a science fair with an emphasis on engineering and design. High school juniors and seniors can attend the STEM Expo, where they hear from professionals in the field and explore careers in science and engineering. And that’s barely scratching the surface.