High Schools Prep Students to Fill Cybersecurity Skills Shortage

Six years ago, during the first cybersecurity course offered at Baltimore’s Parkville High School, a student stumbled upon a mysterious section of the network. “What’s this?” he wondered aloud.

“That’s something you shouldn’t be seeing,” replied Parkville technology teacher Nicholas Coppolino, who runs the high school’s Cisco Networking Academy program. The student had inadvertently hacked into a teacher’s email.

“I read him the riot act,” Coppolino recalls, but it was a valuable lesson. “To protect computers from being hacked, you have to know what the bad guys are doing.”

Coppolino’s students are no longer allowed on the school network during class, but he still teaches them how to think and operate like hackers. Parkville is among a growing number of high schools around the nation offering cybersecurity programs in which students can earn professional certification and college credit.

“These classes are growing exponentially,” says Davina Pruitt-Mentle, lead for academic engagement at the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE), a division of the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

A common template for developing cybersecurity programs is to offer four courses in which students earn industry certification as well as dual or articulated credit that can transfer to a two-year college. By becoming a Cisco Networking Academy, schools can choose from several courses that provide them with industry certification.

.jpg)

“I’m using industry curriculum, so you have to adapt it to fit the level of the students,” explains Bill Tomeo, cybersecurity instructor at Colorado Springs School District 11. In order to prepare students for careers, Pruitt-Mentle also recommends offering other courses that fold in content about how cybersecurity intersects with business, policy or specific industries.

There’s a strong case for such programs. “One only needs to open the newspaper to read about the vulnerability that exists,” says Moise Derosier, career and technical education specialist at the School District of Palm Beach County, in Florida. “We know nationally there’s a need for qualified cybersecurity professionals.”

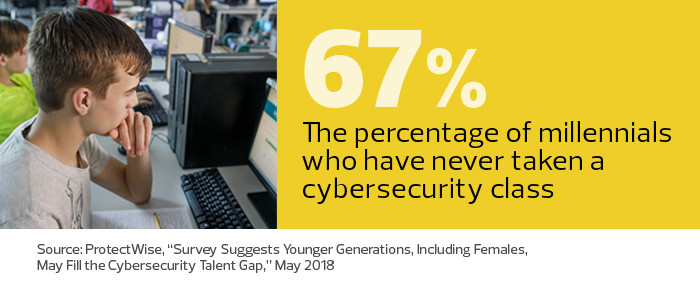

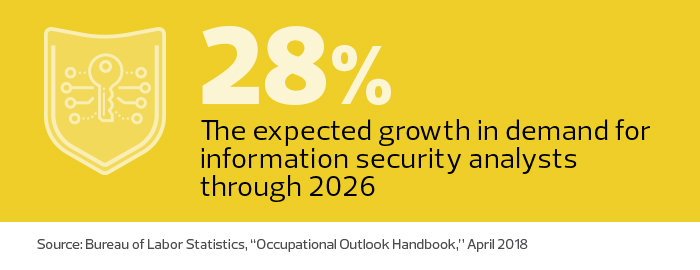

That need is not being met. The cybersecurity skills shortage is projected to lead to 3.5 million unfilled jobs by 2021, analyst firm Cybersecurity Ventures reports. And as demand grows, so do salaries. The median income for information security analysts last year was $95,510 and climbing, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. So K–12 districts like Baltimore County Public Schools, the School District of Palm Beach County and Colorado Springs School District 11 are preparing students for this high-demand field.

In fact, one of Coppolino’s current students landed a paid internship at the National Security Agency with top-secret clearance that is slated to continue into college.

SIGN UP: Get more news from the EdTech newsletter in your inbox every two weeks!

Cybersecurity Courses Offer Opportunities to Grow

Many cybersecurity career and technology education (CTE) pathways offer networking classes that lead to professional certification. Cisco Networking Academy courses — such as IT Essentials 1 and 2, Linux Essentials and Networking Essentials — allow students to earn Cisco Certified Entry Networking Technician and Computing Technology Industry Association (CompTIA) A+, Security+ and Network+ credentials.

Parkville students follow up the IT Essentials class with security and network defense courses. “They learn about configuring hardware and software, firewalls, servers and intrusion detection systems,” says Coppolino.

Districts don’t need to build such programs from scratch. They can adopt curriculum from a variety of government and business resources. For instance, the School District of Palm Beach County’s cybersecurity CTE program is based on a pathway offered by the Florida Department of Education.

The Department of Homeland Security has more curricular resources than any teacher could cover in a four-year program, says Tony Asci, CTE specialist in charge of the district’s cybersecurity programs.

Some students earn college credits while taking cybersecurity classes in high school, while others go directly from high school into the workforce. In cities like Colorado Springs, a hub for cybersecurity, both avenues can be lucrative.

“No one’s going to come out of high school and be a cyberanalyst,” says Bill Tomeo. “But if you have experience in everything from workstations and mobile devices to what you need to do to protect infrastructure, that’s going to give you a leg up into an entry-level IT position and the opportunity to grow from there.”

After participating in a virtual scavenger hunt to track down hackers at the NICE K12 Cybersecurity Education Conference in Nashville last December, representatives from the Palm Beach district decided to bring the activity home. Most faculty and staff found it challenging, but the students breezed right through it.

“The kids were able to solve the puzzles much more quickly than we were,” says Asci.

He sees the students’ success as a testament to the need for programs such as the district’s Cybersecurity Academy, launched in 2016. What started as a single course in an existing IT program grew into a four-year dedicated cybersecurity pathway giving students at four high schools the skills and certification necessary to enter the workforce upon graduation. The district plans to add six schools to the program by 2020.

“It just goes to show you, our students in this day and age are ready for this,” Asci says. “They were born with technology in their hands.”

Reach Broad and Granular Security Needs Through CTE

Cybersecurity education can be useful for students entering fields outside of technology, from human resources managers responsible for hiring and training to medical professionals who must abide by data privacy regulations, says Colorado Springs’ Tomeo.

“The biggest threat in most industries is an employee doing something unconsciously and opening the door to a ransomware attack or taking down the network,” he says. “The growth of the Internet of Things puts even more users and devices at risk.”

NICE’s Pruitt-Mentle applauds states that have begun to overlay cybersecurity into all 16 CTE clusters.

But there’s also a need for specific cybersecurity career–focused programs, she says, particularly those that help prepare students for cyberjobs within a range of career paths. There are seven high-level cybersecurity job functions outlined in the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework: operate and maintain; oversee and govern; collect and operate; protect and defend; investigate; securely provision; and analyze.

Different regions have different needs; for example, D.C. needs defense contractors and Chicago needs manufacturing and control systems specialists. Pruitt-Mentle suggests that schools partner with local businesses and colleges so students can more easily transition from high school into jobs or higher education.

“You don’t want kids taking these classes thinking they’re going to go out and work, and then they can’t work and have to go back to school to do the same courses over again because the classes weren’t articulated,” she says. “You have to look at the data, see where the needs are, see where your partner institutions are and then fit all that together like a puzzle.”

Create Valuable Partnerships With Local Institutions

When choosing locations for its cybersecurity pathway, the School District of Palm Beach County considered which schools had labs with enough computers to accommodate the popular program’s year-to-year growth. “We didn’t want to borrow someone’s lab for one period every day,” says Asci.

Coppolino provides students with routers and switches to use in the networking courses. He teaches in a lab with 18 computers, and because funding is limited, he uses virtual desktops so students can practice hacking different computers and operating systems using the same hardware. Lab activities, he adds, are crucial to a successful cybersecurity program. “If they get hired and they’ve never touched a firewall or a server, they’ll be laughed at,” he says.

Schools with cybersecurity programs also need an infrastructure that will support hacking activities without exposing the district network to mischievous students. When students are using hacking tools, the Palm Beach County district removes machines from Active Directory so all students can access is a sandboxed server or virtual network.

Due to the growing demand for skilled cybersecurity professionals, many businesses and higher education institutions are willing — even eager — to support educational programs by providing donations, expertise and internships for students, externships for teachers and information about emerging trends.

In Baltimore, Parkville High’s students have access to the network labs at Community College of Baltimore County Essex thanks to a partnership between the two schools.

A year before Colorado Springs School District 11 kicked off its cybersecurity pathway, two local firms donated $150,000 worth of equipment to the district, including servers, PCs and network switches and routers.

“We have a lab that’s probably better equipped than a lot of college labs,” Tomeo says. “Students learn better, and they get more excited when they can actually work on gear.”

The district also has spent the past two years working with Pikes Peak Community College — where students can earn credit for taking cybersecurity courses in high school — to build a regional consortium of industry and academic partners. The Cyber Prep initiative, funded by a NICE grant, has brought employers and five local school districts together to ensure that technology education programs are aligned with employment needs.

Resources to Design Cybersecurity Programs Are Everywhere

By partnering with local businesses and colleges, districts can ensure they’re giving students the skills needed by future employers. For instance, because the School District of Palm Beach County is located near Florida Power and Light and Okeelanta Sugar Mill — both of which make heavy use of industrial control systems — the district’s cybersecurity program has a strong emphasis on control system security, says Asci.

Businesses, associations and government agencies also offer a wealth of resources for cybersecurity programs. Microsoft, Cisco, Oracle and CompTIA offer numerous industry certifications, and educators can get ideas and assistance through events such as the NICE K12 Cybersecurity Education Conference and the S4 ICS Security Conference.

“There are hundreds of business partners who have a vested interest in our graduates and are helping us prepare them for the future,” Asci says.

Editors' Note: As this issue of EdTech went to press, we learned of Nicholas Coppolino’s untimely passing on June 10, 2018. Mr. Coppolino was a passionate advocate for cybersecurity education and shared his expertise and inspiration with students at Parkville High School. Our thoughts are with his family, coworkers and students, and we are certain he will be greatly missed.