Career-Focused Schools Use Technology to Help Students Advance

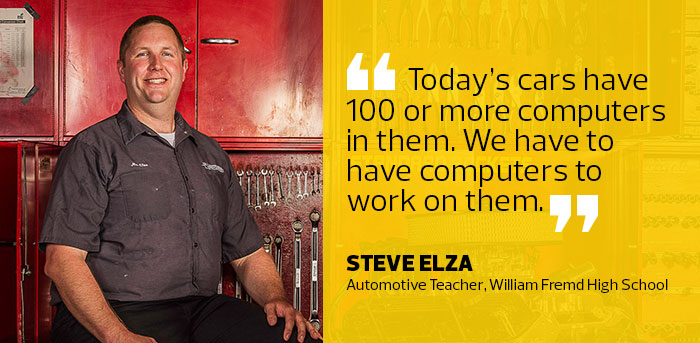

In the past, students in Steve Elza’s automotive classes at William Fremd High School in Palatine, Ill., had to take turns using a diagnostic scanning tool that cost the school up to $8,000. Today, the teens use an inexpensive device that connects via Bluetooth to the tablets they all carry.

“Today’s cars have 100 or more computers in them,” says Elza. “We have to have computers to work on them.” That’s just one of the ways technology is transforming automotive education at Fremd.

When the district deployed tablets, students in career and technical tracks were among the most enthusiastic adopters, says Fremd’s Technology Coordinator Keith Sorensen.

Duncan Polytechnical High School teacher Douglas Urabe (left) and Principal Jeremy Ward (right) have made sure that today’s technologies are used in classes at the school. Photo by Silvia Flores.

“Devices changed the automotive program the most,” he says. “Students film or take photos each step of the way. They are really good at documenting their work and explaining it.”

Elza, who also coaches the school’s Hot Rodders of Tomorrow team and was named the 2015 Illinois Teacher of the Year, says all the software the students use is online.

“When they look up a torque spec for a brake system, they use our online software and find that information right on their tablets,” he says. “They also use computers to do 3D modeling of parts.”

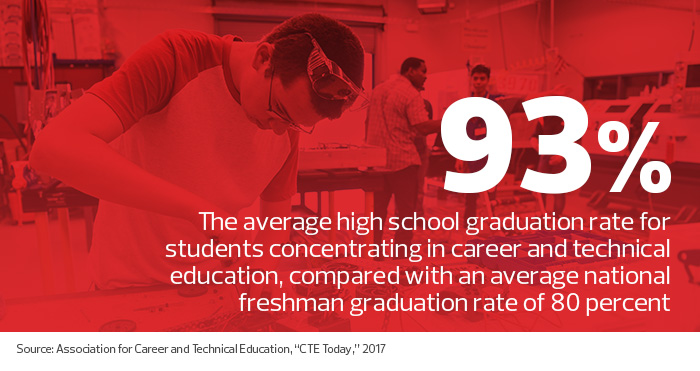

In addition to automotive classes, Fremd offers students the chance to learn about building construction, engineering, electronics and woodworking. This sort of applied technology instruction was once called “vocational,” and it was seen by many as a place to put students with limited academic skills.

But today, career and technical education programs prepare students for both college and the workplace. (Some of Elza’s students go to $18-an-hour jobs after graduation, while others pursue four-year degrees.) And, as many of these career paths become more technical in nature, school districts are investing in technology to help their students keep pace with career demands.

“If we look at hiring trends for well-paying career jobs, we’re seeing employers care more about whether students can demonstrate what they can do, rather than what they have on a piece of paper,” says Richard Culatta, CEO of the International Society for Technology in Education. “The students who are best positioned for good jobs are the students who can demonstrate both,” he says.

Practical IT Applications

Often, the words “instructional technology” recall the ways that devices and applications can help enhance traditional academic subjects such as history and English. In fact, the hands-on, practical nature of most career and technical education subjects means that tech tools are not just a fit, but a necessity.

“What I get excited about is using technology as a tool to create and design and solve problems,” says Culatta. “That’s what happens in these practical, career-focused skill areas.”

At Duncan Polytechnical High School in Fresno, Calif., educators use a variety of technical tools to support career pathways such as automotive, construction, welding, nursing and rehabilitative therapy.

“People conjure ideas of [linemen] working on assembly lines when they think about manufacturing,” says Jeremy Ward, principal at Duncan. “That’s not manufacturing in our country today. Manufacturing today is sophisticated and complex, requiring the skills of technically savvy and competent individuals.”

Building a Solid IT Foundation

Douglas Urabe, a manufacturing teacher at Duncan, says that companies don’t expect graduating students to have mastered specific skills related to the field. Rather, he says, employers are interested in students with a solid foundation in IT who continue to learn and adapt.

“They want to see students get exposure to technology, and then refine their direction and get more specialized, intensive training,” Urabe says. At Duncan, students use a combination of traditional classroom technology and career-specific tools. Each of the school’s career pathways classrooms has a computer for every student, and students use Google Drive to work on interdisciplinary projects.

“They can write the report in automotive class, and then edit it in English class,” says Beau Sunahara, an automotive teacher at Duncan. “They can share documents with each other if they’re doing collaborative work.”

Students in Duncan’s manufacturing program also use computer-aided design software to build 3D models of objects — for example, a puzzle composed of 27 wooden cubes — and then bring their designs to life with 3D printers and computer numerical control milling machines and lathes.

Keeping Pace with Industry Tech Updates

The automotive industry has changed, and thanks to technology, students will be able to keep pace, Ward says. “It’s not like it was before, where you just learned how to turn a wrench or how to rig something together. There are precise requirements to get things done accurately. We’re not going to be preparing our students to be successful if we’re just doing things how they were done 40 and 50 years ago.

“Machines today are extremely complex,” he adds. “Not only do students need applied technology skills, but they also need to be good problem-solvers, which is perhaps one of the best transferable skills to have.”

Infrastructure investments are critical to supporting the end-user technology in career and technical education programs. Fresno has made many upgrades in recent years, including the implementation of Wi-Fi on school buses. Fremd, for its part, recently refreshed its servers and Wi-Fi network, and it is poised to invest roughly $500,000 in security and power solutions.

“We’ve always taken care of the infrastructure first before adding devices, and that’s a huge help,” says Fremd’s Sorensen. “The last thing you want is a situation where every student has a device, and they can’t get on the internet.”

Preparing Students for College and Careers

Forsyth County Schools in Georgia offers a variety of career and technical education tracks, including automotive, culinary and cosmetology programs. Jim Tozier, an instructional technology specialist for the district, illustrates the choices available to students by giving the example of his own twins, who are students in the district.

While Tozier’s daughter is an honors student and took biotechnology coursework in high school, his son studied in the automotive program. Both have several attractive options for pursuing higher education, including scholarship offers (although Tozier’s son may first serve in the military).

“In the past, back when I was in school, and even when I started teaching, most career and technical programs were geared toward students who were not going to college,” Tozier says. “Now, a significant portion of the students are going to at least a two-year school, if not a four-year school.”

Making the Most of BYOD

Forsyth has a bring-your-own-device program, and Tozier says that students often download and create videos with their smartphones — first to help them to attain content mastery, and then to demonstrate that mastery.

When students have trouble perfecting a hands-on process — anything from applying makeup to rotating tires — they can use their phones to watch instructional videos online. Then, when they have mastered the skill themselves, they make their own videos, which teachers collect in digital libraries to show to future students.

“It has helped students to develop digital portfolios, so they can show prospective employers that they can do these particular techniques,” Tozier says.

Elza says he feels like a “proud papa” when he sees students at Fremd figure out how to do something new by conducting research with their mobile devices, rather than relying on him for answers. Many students, he says, take their digital portfolios to job interviews.

“It’s pretty amazing when the students come back to you after they graduate,” Elza says. “Sometimes you run into a former student who says, ‘If I hadn’t taken this class, I’d be in a far different place.’”