“It’s a great opportunity, not just focusing on four-year graduation, but looking at students who are graduating in four and a half years and those who are graduating in five, and seeing what it was that threw them off by one semester and what kind of barriers we can remove to change that,” he says. GSU takes a similarly broad view.

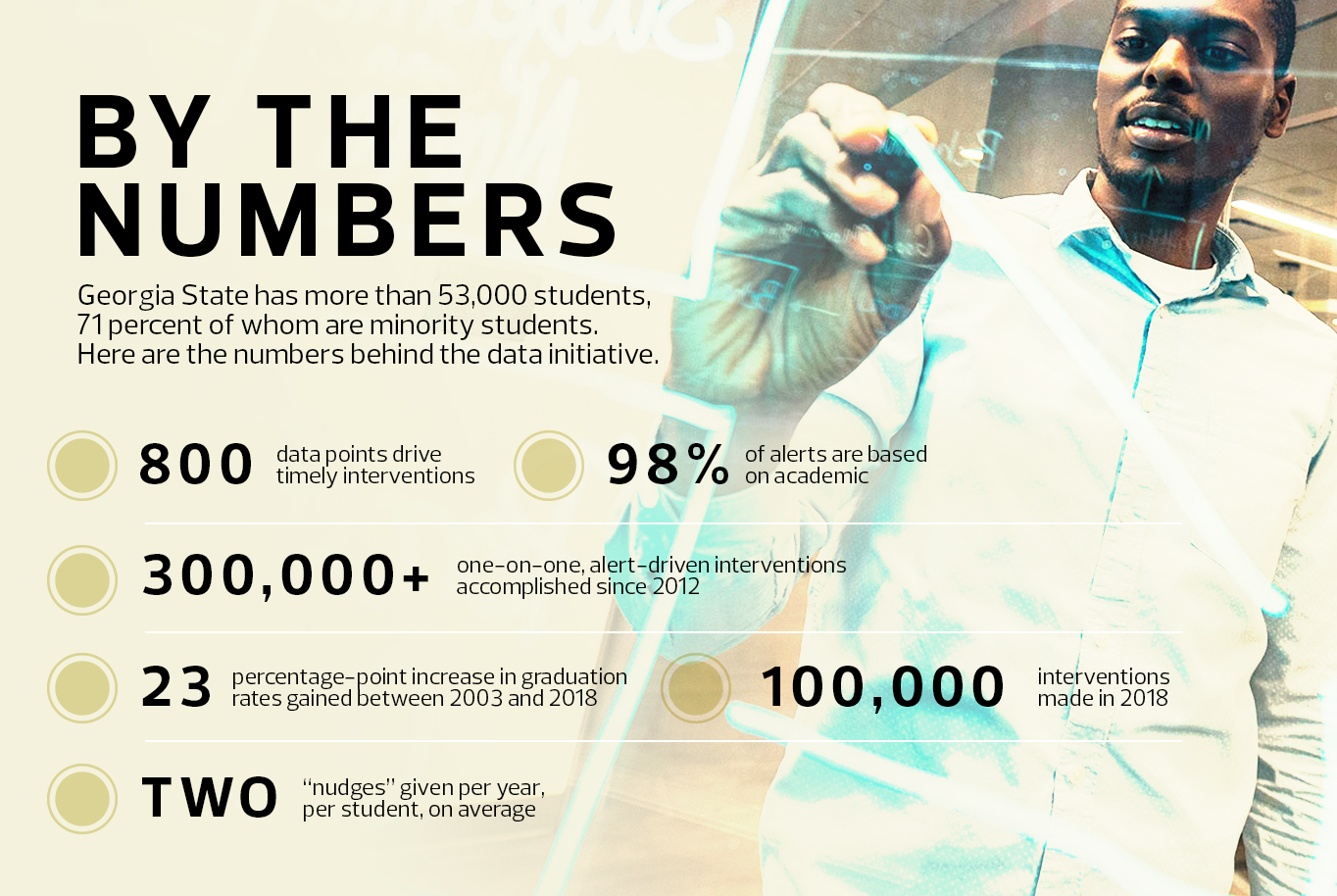

Its staff analyzed 10 years of data, including 2.5 million grades and 140,000 student records, searching for data points and identifiable behaviors that correlated to dropout rates in a statistically significant way.

They expected to find a few dozen. Instead, they found 800. A direct correlation exists, for example, between dropout rates and midsemester course withdrawal. A student’s electronic footprint might indicate a problem: If he isn’t logging in to the Wi-Fi network, he probably isn’t attending classes. Today, those data points drive timely supports.

“If any of those 800 behaviors is identified, the adviser assigned to that student gets an alert, and they have 48 hours for an intervention,” Renick says. “They call the student in, sit down and meet face to face with the students to try to help with whatever they can.”

At Long Beach, the four-year graduation rate has jumped from 16 percent to 28 percent in the past two years, with a goal of 39 percent by 2025. Meanwhile, gaps in the graduation rate have dropped from 12 percent to 4 percent for minority versus nonminority students and to 7 percent for Pell recipients versus non-Pell recipients, respectively.

Universities Develop Data Platforms to Find Identify At-Risk Students

The technology behind GSU’s program is a platform from the EAB (formerly the Education Advisory Board) that taps into GSU’s student information systems for data on its 53,000-plus students. For example, the platform might alert an adviser that “Sue Jones just failed a math quiz” so he or she can recommend that Sue attend a free tutoring course.

GSU also developed an in-house system to track class attendance by monitoring logons to the Wi-Fi and learning management system. A data platform predicts demand for certain courses so the university can ensure enough seats are available, and a custom chatbot powered by artificial intelligence answers students’ questions about admissions, enrollment and other tasks.

MORE FROM EDTECH: See how one university used data analytics to slash student failure rates.

Colleges’ Commitment to Graduation Attracts Parents’ Attention

GSU also boosted graduation rates by targeting students’ financial issues. Every semester, approximately 1,000 students dropped out — not because of grades, but because they couldn’t pay all of their tuition.

Today, GSU uses microgrants to keep these students enrolled, depositing small sums into the accounts of students nearing graduation. In the past seven years, GSU has distributed more than 13,000 Panther retention grants, and 87 percent of recipients have gone on to graduate.

“We are tracking the students carefully. We know just how much they owe,” Renick says. “But we also know which students have a high probability to graduate, and a senior who has almost gotten to the end has shown grit.”

Long Beach made a similar discovery, says Sathianathan. Once staff realized it was often money, not academics, that pushed students into an extra year of classes, they set out to change that.

An investment of $200,000 has increased the university’s four-year graduation rate by 4 percent, Sathianathan says.

At GSU, GPS Advising not only saves money, it also generates it, according to an analysis conducted by Boston Consulting Group. It found that the program has generated more revenues than it has cost by retaining students who otherwise might have left, Renick says.

The program’s success is also attracting new enrollments, he adds. “We’ve had parents who have told us that they are specifically enrolling their students at Georgia State because they’re investing a lot in the education and they want to make sure that the students have the maximum chance of sticking with it and graduating.”