Teachers and Tech Teams Collaborate to Ensure IT Success

As the IT team in the Peabody (Mass.) Public Schools devised a new technology plan several years ago, staffers didn’t rely solely on their own tech expertise or ask outside consultants to tell them about software and hardware trends in K–12 education.

Instead, they visited the schools and talked to the people who ultimately would have the most significant impact on the success of any new technology rollout: the teachers.

“Instead of the IT team making decisions and assuming it was going to work, we asked, ‘What does your ideal classroom look like?’” recalls Marc LeBlanc, assistant IT operations manager.

Since that time, the district has created a formal Information, Communication and Technology committee to help bridge the gap between IT staffers and classroom instructors. Technicians from the IT department are a part of the group, alongside media specialists and classroom teachers, all of whom meet to discuss the instructional impact of technology.

“We’re able to look at the needs of teachers and at what types of technology will best support learning in the classroom,” says Jarred Haas, a digital learning coach. “We consult with teachers on a regular basis. Any time we make a decision, it will go before teachers first.”

While it may seem obvious that IT and curriculum departments should maintain constant communication to ensure that technology supports instruction, in reality that doesn’t always happen. Too often, technology simply shows up in classrooms, and teachers either poke at it and try to figure out how to use it or allow it to collect dust in a corner. In other districts, teachers receive training on how to use the tech tools but perhaps have little input during the selection and purchase process. That’s why some school districts create formalized teams like the one put in place by Peabody Public Schools — to guarantee meaningful, ongoing dialogue that ensures instruction remains the top concern during any tech rollout.

Forgo a Tech-Centered Approach

As director of digital literacy and innovation for Community Unit School District 300 in Algonquin, Ill., Anne Pasco straddles the line between IT and academics daily.

She says it’s understandable — though certainly not ideal — that K–12 curriculum and IT departments have, at times, remained in their own silos. Technicians often spend a lot of time running from location to location, helping users to solve problems; and many teachers find it difficult to dedicate time during the school day to eat lunch, let alone communicate with IT about potential tech investments. But some observers say there’s a growing awareness in schools that tech initiatives simply won’t find success unless and until teachers are brought on board.

“Early on, I think there was too much bright-and-shiny-object syndrome,” says Jim Flanagan, chief learning services officer with ISTE. He says that during the early days of one-to-one device programs, many schools initiated large-scale deployments of tablets or notebook computers without pausing to get feedback from instructors.

“With the best of intentions, people were excited about the potential of the technology, and they were getting it into the hands of teachers and students as quickly as possible,” Flanagan says. “Now, I think we’re definitely moving in the right direction of getting more educator input.”

Photo by Darren Hauck

Making Decisions From the Bottom-Up

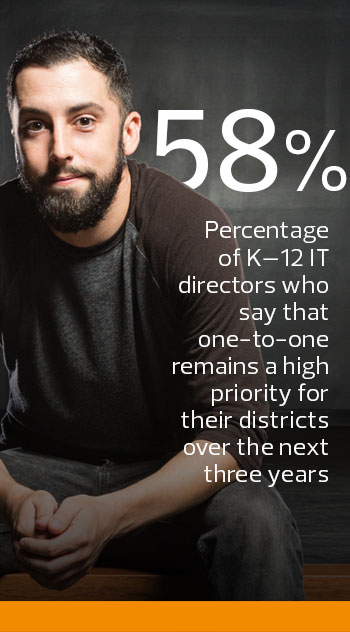

Perhaps no decision has a broader or longer-lasting impact on a school’s IT culture than what device to distribute to students in a one-to-one initiative. While many schools previously made those decisions in a top-down fashion, administrators more frequently seek input from teachers, allowing them to test different devices in their classrooms to discover which will help them best meet their instructional goals.

Back in Peabody, teachers played an integral role, both in device selection and in the classroom instruction angle.

Chris Mitchell, IT operations manager for the district, says administrators leaned strongly toward a tablet deployment, but many teachers stressed the importance of having a device with a physical keyboard. Other teachers sought devices with touch screens to allow students to manipulate virtual objects, use educational mobile apps and draw on screens the same way they would draw on a whiteboard.

“In the two years that we were developing a plan, the Chromebook became a viable option,” Mitchell says.

Ultimately, the district opted to deploy Acer Chromebooks to 1,400 middle school students, and another 400 to 9th graders, along with in-school carts of touch screen–enabled Chromebooks for teachers to use as needed.

“That was something that we probably wouldn’t have done if we hadn’t heard from the teachers,” LeBlanc says.

At the elementary level, the district initially planned to roll out mobile Chromebook carts that teachers could reserve. “But when we spoke with teachers, they said, ‘We would much rather have four Chromebooks in each room, so that the kids can share and work together,’ ” LeBlanc says, adding that IT adopted the teachers’ plan.

Over time, Mitchell says Peabody has moved toward more collaboration and standardization across the district, as opposed to each school rolling out different types of technology.

“We’ve developed this plan now that’s ensuring the technology will be refreshed properly, and that everyone has the same equipment from the middle school to the high school,” he says.

Maine School Administrative District 51 (MSAD 51), which includes the towns of Cumberland and North Yarmouth, formed Teacher Tech Teams in each of its schools. The state of Maine has funded notebooks for middle school students for several years, and in 2013 gave districts the option of sticking with notebooks or shifting to tablets.

“I thought that the tablet would be the best solution,” says Dirk Van Curan, the district’s technology director.

But teachers in the district were split: Half wanted to move to tablets, and half wanted to stick with notebooks. Members of the Teacher Tech Teams argued that notebooks would provide instructors with a better opportunity to more fully integrate technology into their classrooms because they were already familiar with the devices. The district stayed with notebooks, and Van Curan says that decision has worked out well.

“I was overruled by the Teacher Tech Teams, and I’m thankful for that,” he says.

Teachers Teaching Teachers MSAD 51 didn’t switch away from notebooks, and Van Curan didn’t need to train teachers on the basics of the device. Instead, he relied on the members of his Teacher Tech Teams to lead professional development sessions on how to leverage the devices to incorporate educational tools like Google Classroom, Evernote and Newsela. The teacher leaders sat at tables advertising each solution, and the rest of the teachers decided which tools they wanted to learn about.

“The principal received the best feedback around, because people got to choose and they worked with other teachers who are in the trenches with them,” Van Curan says. “It wasn’t me trying to teach everyone why they should use a certain app.” Similarly, Pasco in Illinois manages a team of digital learning specialists — former teachers who coach other instructors on how to best use technology for instruction.

“They’re not the people who are going to fix your computer if it’s broken,” she explains. “You call them and say, ‘This is what I’m trying to accomplish in my classroom. How do I set up this software to do that?’ ”

When professional development fails, Pasco says, it’s often because the training focuses on devices more than instruction. “When the training revolves around the technology, that’s a problem,” she says. “The training has to involve instructional practices supported by the technology.”

Building Consensus Between Stakeholders

It’s virtually impossible to get every teacher in a district to agree on a single device or software program. But when instructors are involved in the decision-making process, they at least feel as though their concerns are being heard.

Pasco’s district opted for a one-to-one Chromebook rollout, and although there were some dissenters, she says that most people are on board with the decision. “We didn’t get a ton of pushback,” she says. “I haven’t had anybody stomping their feet and screaming and yelling.”

Todd Bucey, principal of Higgins Middle School in Peabody, says that involving teachers in decisions has the potential to increase IT adoption rates.

“You’re making a decision that the whole team stands behind,” Bucey says. “You’re not just getting feedback here and there. You’ve got a decision that’s made by the team, and I think that carries a little more weight.”

SOURCE: MDR, “State of the K–12 Market 2015,” January 2015

Pasco sums it up simply: “Curriculum drives technology. Technology should not drive curriculum.”