Stanford University’s Artificial Intelligence Summer Camp Expands the World of Computer Science

The Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory’s Outreach Summer (SAILORS) program was born in 2014 when then-Ph.D. student Olga Russakovsky was in search of a way to make an impact outside of writing another research paper.

What she and Fei-Fei Li, director of Stanford University’s Artificial Intelligence Lab, created was a two-week summer day camp for 10th grade girls centered on how artificial intelligence can change the world. This July marked the second year of the program.

“It seems like a lot of girls are interested in these fields, but then drop out as their education progresses,” says Russakovsky. “We created a camp centered around teaching AI from a humanist prospective.”

Russakovsky, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Mellon University, says the camp aimed to address three things: the lack of exposure to technology in early education; the lack of role models and social support for young women; and the limited perception of what computer science can do in the real world.

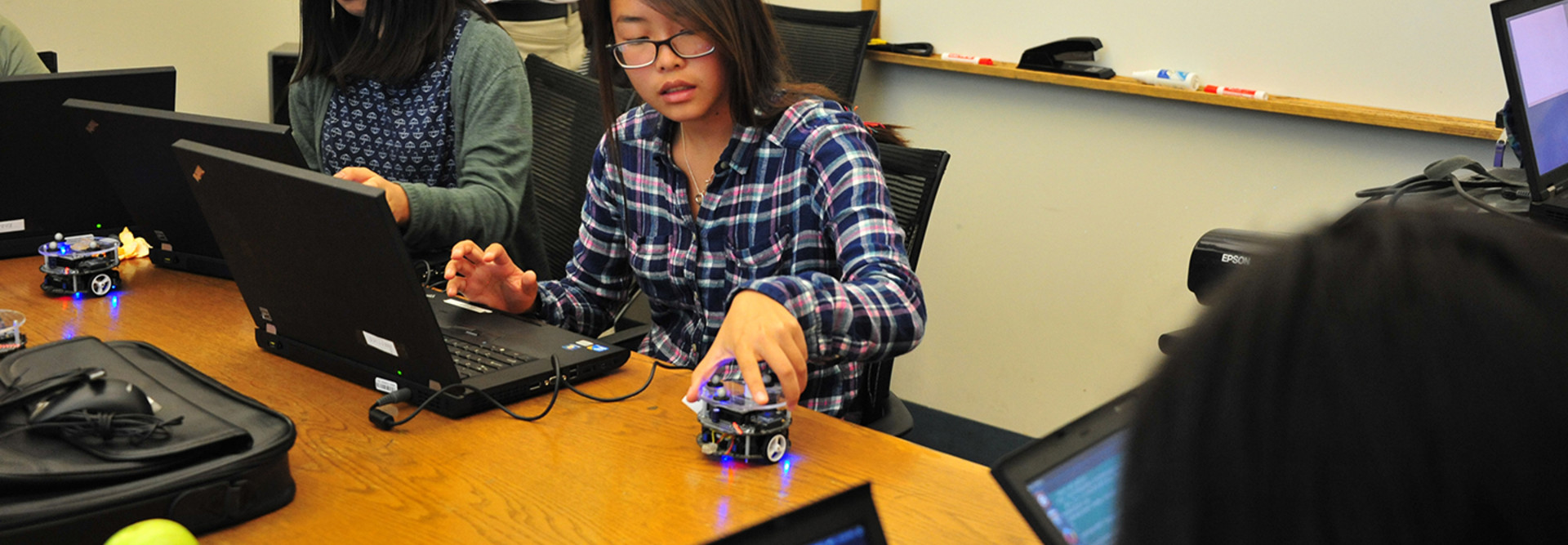

Stanford, with the help of sponsors Dropbox and Google, provides the technology behind the camp, which ranges from the simple (paper and pencil) to the very complex (robotics and drones).

As recorded on the camp’s daily blog, participants experimented with proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers, which are used to steer hexacopter drones, and got hands-on coding experience coding using Lenovo ThinkPad notebook computers to analyze data and power small robotics. Campers even learned how Standford’s self-driving car works.

Learning How AI Can Help Real People

A big goal of SAILORS is to reframe how computer science, and AI in particular, is perceived, Russakovsky says.

“It’s about reframing the conversation with AI instead of focusing on the money that can be made or the very few applications that are shown in the media,” she says. “It’s not about creating killer robots, but how it can actually benefit society. Women tend to be drawn to this kind of perspective.”

While studying what is hot in the tech world, these girls are also working on incredibly innovative research in robotics and computer vision — how computers can analyze and understand digital images.

In their research paper following the first year of camp, Russakovsky and her colleagues detailed the young women’s research into how certain computer vision algorithms can ensure hospital staff are sanitizing their hands, and how natural language processing can examine tweets during a natural disaster to assist with organizing aid.

“The research projects were designed to closely mimic current AI research. Students could thus get a first-hand experience of what researchers in the field work on, and gain confidence that they can work on the same,” the paper reports.

Creating an Environment for Collaboration

In order to retain women in STEM education, educators must help them find peers and establish role models, Russakovsky says.

In addition to the staff from Stanford’s AI Lab, Russakovsky says the camp is run almost entirely by undergraduate and graduate student volunteers. So while the young camp participants are gaining a valuable social experience by meeting fellow STEM aficionados, the Stanford students are honing their teaching skills and learning how to present their complex research to high schoolers.

“It actually serves as a great community building effort for the lab. There’s not much interaction between the faculty and the students. [The camp] is something the entire department rallies behind,” Russakovsky says.

The Beginnings of a New Countrywide STEM Initiative

In our Summer 2016 issue, EdTech reported on how Merced Union High School District’s rollout of Chromebooks helped to provide STEM opportunities to underserved children.

Russakovsky’s hope is that this camp will do the same to empower young women into exploring their passion for technology.

Initially, after reaching out to Bay Area high school teachers, Russakovsky wrote on her website that they received over 200 applications for the 9-to-5 day camp’s 24 slots.

Next year, she proudly reports that the camp will be residential, which will open it up to students from all over the country.

Russakovsky, who is joining the faculty at Princeton University, plans to launch a sister program to Stanford’s camp in 2017.

“We want to figure out how to generalize SAILORS and create a model for other universities to create similar programs,” she says.