TCEA 2014: Teachers Can Help Students Preserve Their Dignity in the Face of Bullying

It’s unseasonably cold in Austin, Texas, this week, but the 13,000 educators, vendors and thought leaders who have gathered here for the Texas Computer Education Association (TCEA) 2014 convention and exposition are all fired up. A last-minute change in opening keynote plans — scheduled speaker John Quiñones, anchor of the ABC News program “What Would You Do?”, will present on Friday morning instead — didn’t dull the enthusiasm of the crowd, who welcomed celebrated author and speaker Rosalind Wiseman to the stage.

Wiseman, a Washington, D.C., native and former teacher, is perhaps best known for her best-selling 2002 book, Queen Bees and Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends, and the New Realities of Girl World — the basis for the 2004 movie Mean Girls — and for developing the Owning Up Curriculum, a structured program that teaches students in grades 6 through 12 “to own up and take responsibility — as perpetrators, bystanders, and targets — for unethical behavior.”

The latter topic — in particular, the responsibility to treat others with respect and dignity — drove Wiseman’s remarks to conference attendees. Here’s an overview of the key insights she shared.

Boys Need to Be Heard Too

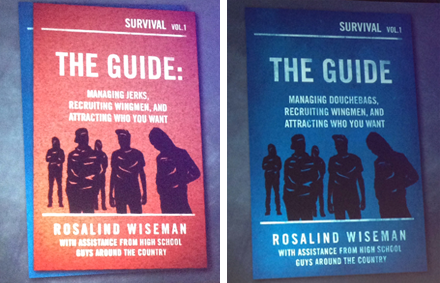

Wiseman has written about girls (in the aforementioned Queen Bees), parents (Queen Bee Moms and Kingpin Dads: Dealing with the Parents, Teachers, Coaches, and Counselors Who Can Make — or Break — Your Child's Future) and, more recently, boys (Masterminds and Wingmen: Helping Our Boys Cope with Schoolyard Power, Locker-Room Tests, Girlfriends, and the New Rules of Boy World). In addition, she authored a free companion e-book for boys called The Guide: Managing Douchebags, Recruiting Wingmen, and Attracting Who You Want and a school edition with a slightly different title, The Guide: Managing Jerks, Recruiting Wingmen, and Attracting Who You Want. Both were written in collaboration with more than 200 middle school– and high school–age boys over a two-year period “to chart the emotional terrain that boys inhabit.”

Wiseman conceded early in her remarks that she doesn’t think she “has the right to speak for boys. I visit adolescent culture quite a bit, but it doesn’t make me an expert. But I can listen to what they’re going through.”

From her conversations with these young men, Wiseman continued, she discovered that “boys are sneaking each other all the time. They’re festering inside about the experiences they’re having that are important to them, but they don’t feel like they can talk about it.”

But even when teachers, administrators and school staff can’t help a male student “solve” a problem, she said, it’s important that he be given the opportunity to communicate it — when he’s comfortable and in his own way.

Four Ways to Motivate Students

Every young person has his or her own strengths and weaknesses — and will sometimes struggle in school. But educators can help students find ways to succeed by giving them opportunities to achieve or embrace what Wiseman called “the four tenets of happiness”:

- Finding meaning beyond one’s self

- Hope of success

- Social connections

- Satisfying work

“If we can get young people to think of [education] that way, school gets more interesting,” she said.

Conflict Is Inevitable, But Dignity Is a Right

Bullying is a growing problem in schools. “No matter how good the school is,” Wiseman said, “students will experience conflict while they’re there. School is all about group dynamics, about navigating it competently.”

The adults who work in schools have good intentions when they intervene in student conflicts. But often, what they say and how they behave doesn’t achieve the desired outcome. If the persecuted student is singled out in a group setting, Wiseman explained, that added attention can sometimes make the student feel worse or lead him or her to presume that the teacher coming to his or her aid is incompetent.

In the moment of confrontation, Wiseman said, adults should do four things:

- Assess the situation on approach

- Don’t ask the group who’s responsible for the situation

- Get the group on task (by exiting the hallway and heading to their next class, for example) and promise them that teachers will follow up with the bullied student later, when he or she is alone

- Assess the situation as everyone disperses to determine what else might need to be done

In every situation, Wiseman added, the goal should be to preserve every student’s dignity. “Respect is earned, but dignity is a given,” she said. “One of the problems we have with our credibility in schools is that we don’t acknowledge that young people are regularly having interactions with adults who don’t merit their respect. If young people have adults in their life who are degrading to them, that child shouldn’t respect those adults.”

The same logic applies to student-on-student degradation, she continued. “Kids can be cruel. If students say, ‘That’s what we do’ [to justify their bad behavior], you should say, ‘Why?’ Just because it’s common doesn’t make it right.”