If ever there was a time for IT departments to shine, this is it. Even before the pandemic forced a transition to remote learning in March 2020, universities were increasingly recognizing the critical role that technology will continue to play as the future unfolds. The role of CIO had already reached ubiquity on higher ed campuses. Schools were increasingly exploring online learning options and cloud transitions. Discussions around digital transformation gained steam, even if the path forward seemed uncertain (and, in some cases, underfunded).

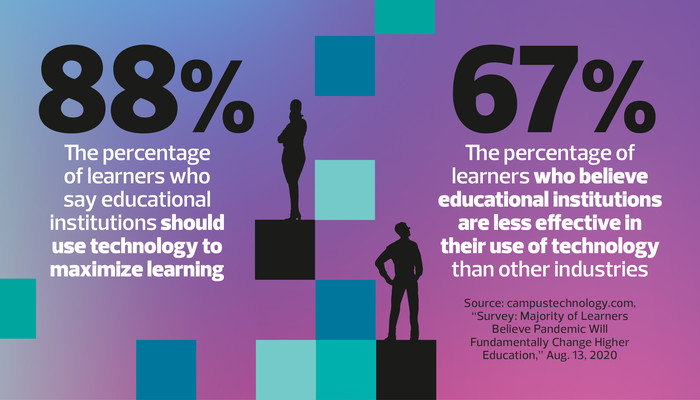

Then came COVID-19 and, with it, heightened concerns about declining enrollment numbers and questions from students about whether their degrees would be worth the tens of thousands of dollars they’d spend to earn them. Throughout these conversations, a common thread emerged: Technology would play a significant role in answering these questions and solving the problems behind them.

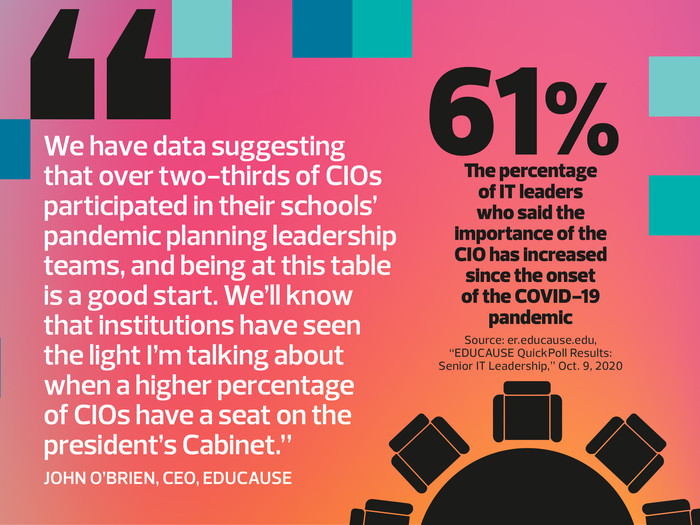

“Technology innovation helps campuses solve the institutional grand challenges that keep presidents awake at night,” EDUCAUSE CEO John O’Brien tells EdTech: Focus on Higher Education. “Technology innovation is becoming a differentiating value for institutions and a path to achieving institutional goals and stability.”

Between the pandemic-prompted transition to remote learning and the recognition that higher education needed to evolve, university leaders have overwhelmingly come to the same conclusion: Digital transformation is no longer a luxury — it’s an imperative.

MORE FROM EDUCAUSE CEO JOHN O'BRIEN: "Use DX as a springboard to strategic IT."

“Digital transformation might have seemed like a rhetorical flourish before, but now it’s so clearly real,” O’Brien says. “It’s not just a lifeline that got us through a tricky situation. It is and must increasingly be understood as an integral, strategic part of the successful college or university.”

The Mainframe: An Academic Beginning for Tech in Higher Ed

Long before iPhone devices or Chromebooks, there was the mainframe. And nowhere was the mainframe more deeply rooted, more essential or more influential than in higher education.

Indeed, the first mainframe was even named for the oldest university in the United States. Developed and built by IBM, the Harvard Mark I was installed at Harvard University in 1944, where it was first used to conduct computations for the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Ships. Over the following several decades, mainframes were installed at organizations around the nation, finding a particular degree of usefulness at colleges and universities with large grants funding academic research. However, often weighing several tons and built with hundreds of thousands of components, mainframe computers required a lot of manpower to program and operate.

And thus, IT began making its entrance into the realm of higher education (along with numerous other industries).

When Academics Held the Keys to the EdTech Kingdom

Technology has long held a role in classrooms. Indeed, in 1870, classrooms were first introduced to the magic lantern, a primitive type of slide projector that was ultimately replaced by the first overhead projector in the early 1900s.

Susan Grajek, vice president for partnerships, communities and research at EDUCAUSE, remembers waiting for her turn to use Yale University’s mainframe computer at the Yale Computer Center in 1979, when she was a graduate student working on her dissertation. Back then, she recalls, university mainframes — or at least the resources dedicated to programming and operating them — were largely attached to research grants.

When the funding for a specific project ran out, schools found themselves left with mainframes they still wanted to use. To that end, many schools adopted time-sharing programs, which allowed academic users to take turns using computer terminals connected to the mainframe.

These machines, however, needed someone (often several someones) to manage and operate them. At Yale, Grajek remembers, a professor she worked with received a large grant from IBM for a mainframe-based project.

“He said, ‘Stuff needs staff,’” she recalls. “Very often, it was a faculty member who knew the most and who had the most stake in computing at the institution and with operating the mainframe. So, when institutional leadership wanted to continue using the mainframe after the grant expired, they needed to put somebody in charge of it. It was usually a technically oriented faculty member —often a computer scientist, sometimes a mathematician, sometimes a physicist — but usually from these very computation-heavy departments.”

RELATED: In post-pandemic higher education, Plan B matters as much as Plan A.

These faculty members, Grajek explains, were the historical precursors to the modern CIO. “They were primarily academics, primarily professors, not managers. But they were the people who had kind of the keys to the kingdom, if you will.”

Cloud, EdTech and a Strategic Place at the Leadership Table

Countless technological innovations have emerged in the years since Grajek sat in line at the Yale Computing Center, waiting for her turn to access one of the computer terminals attached to the university’s mainframe. For higher education, she says, the introduction of microcomputers (and then personal computers) on university campuses proved to be a watershed moment.

“Suddenly, users owned their own computing environment,” Grajek says. “And it didn’t take very long before people in humanities disciplines also wanted to use these machines.”

Tensions emerged, she explains, as universities and their constituents tried to determine who, exactly, controlled computing environments. “Was it the end user or the institution?” Grajek says.

At the same time, the nature of IT — and what actually constitutes IT — was changing, and with it the role of the IT professional, says Kevin Morooney, vice president of trust and identity and NET+ programs at Internet2, a nonprofit organization focused on providing a collaborative networking environment for U.S research and educational institutions.

There was a time, Morooney says, when IT was a more defined, specific concept with a more limited scope. In 1985, for instance, there weren’t nearly as many IT roles, he explains. Those that did exist were mostly responsible for simply managing and servicing the technology in place. Today, however, IT touches every industry and every activity in which people engage.

“I don’t know what you mean anymore when you say IT,” Morooney says. “IT could be in the grocery store. I could be traveling in an airport. Do they mean the update on their phone doesn’t work? Did they mean they couldn’t print something? They mean all of those things.”

Not only has the nature of what constitutes IT broadened in scope but the number of IT jobs has expanded, and the types of roles that exist have increased too. A single IT department might have multiple specialists, each responsible for a specific element of the network or software or security.

A Remote Learning Pivot and an Accelerated Rate of Change

The purpose and expectations of higher ed IT departments had been gradually evolving for years when the COVID-19 pandemic swept the U.S. in early 2020, forcing college campuses to transition to remote learning practically overnight.

“Acceleration, by definition, is the rate at which change changes,” Morooney says. “The rate at which information technology is changing is not really even conceivable by humans. We can’t completely wrap our minds around it.”

MORE FROM EDTECH: Here's how the shift to remote learning could reshape higher ed IT.

The pandemic, he continues, acted as an accelerant for “phenomena that were happening anyway, but that had been happening very slowly. Any time you’re challenged with a new risk, you proceed cautiously, right?” But the pandemic, Morooney says, forced higher ed IT departments to abandon some of that hesitancy.

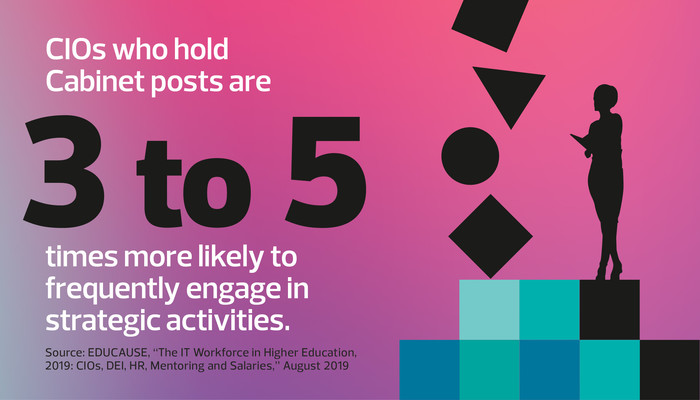

For colleges and universities that had been adopting and embracing the importance of IT gradually over the course of years, the concept of digital transformation evolved from luxury to necessity almost overnight. In turn, the role and influence of higher ed CIOs has grown as well.

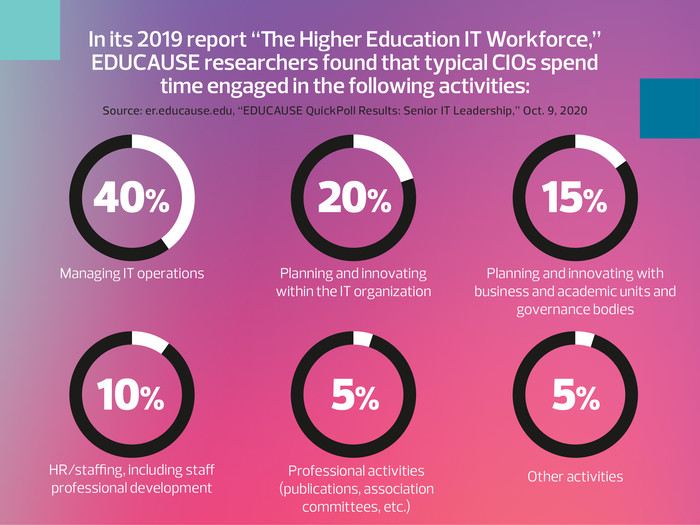

Making the Most of IT's Growing Strategic Influence

Even with postsecondary schools gradually bringing students, faculty and staff back on campus — and, they hope, back to the traditions considered inherent to their value propositions — there’s also a realization that the higher education experience has been indelibly changed. Meanwhile, the role of IT departments is changing as well.

“The COVID crisis has added a gigantic exclamation point to the message we’ve been stressing about the strategic role of IT for years,” O’Brien tells EdTech. “The utility thinking that was instrumental to the rise of IT in higher education is not the kind of thinking that will take us into the next decade.”

While university responses to COVID-19 brought increased prominence for higher education IT leaders, their place at the boardroom table won’t disappear when the pandemic subsides. The imperatives around digital transformation and technology’s role in postsecondary value propositions are likely to remain a fixture, albeit an evolving one.

This leaves higher ed IT departments with an opportunity to continue refining their presence and the role they play in myriad aspects of their universities’ strategies — from student success to enrollment, retention and more.

EXPLORE: Read University of Delaware CIO Sharon Pitt's advice for strategic IT.

KEEPING UP WITH EDTECH: Follow us on Twitter.

One of the most important steps that university IT teams can take to continuously prove their strategic merit is to demonstrate a thorough understanding of what their different users actually need, Morooney says.

“In the past, IT professionals weren’t there to help people extract value from the technology,” he says. “They were just running it.” But today, he continues, “IT teams need to understand both the technology and the outcome that users are trying to achieve with it.”

Listening, he says, can play a significant role in achieving that level of understanding. “One of the key skills of a good IT professional is understanding what people are working with and what they’re trying to express,” Morooney says.

“Your users don’t know what you know. You need to be kind and you need to have the skills of a good therapist. Let them talk about their needs and get everything on the table. Then, you can take what you’ve learned from them and repackage it in a way that might help them make sense of how to leverage all of these capabilities.”