The ABCs of BYOD on Campus

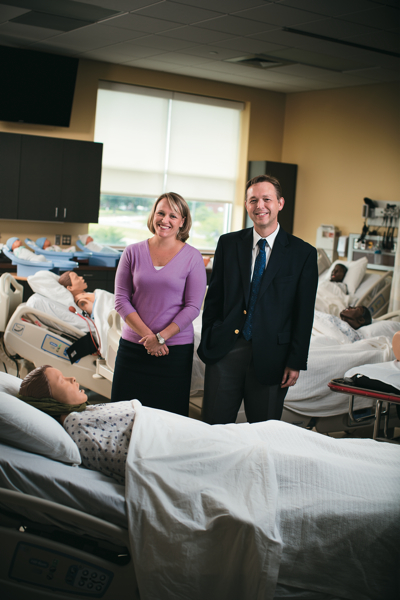

Credit: Charles Harris

Mary Wymbs and Jeremy Campbell encourage Rowan-Cabarrus Community College students to bring their own devices, but agree that BYOD means more than just welcoming those devices on campus.

When Jeremy Campbell joined Salisbury, N.C.'s Rowan-Cabarrus Community College (RCCC) as the CIO three years ago, he found he had his work cut out for him. Students there didn't have user accounts, so they couldn't access educational resources on the network. Staff couldn't make IP calls from one campus to another. Some users couldn't even access the Internet in many areas.

"It was really like walking into 1994," Campbell says.

As he dug into his work, he found that what at first appeared to be his biggest challenge turned out to be his greatest advantage: "We didn't have to worry about carrying any legacy architecture forward. We had an opportunity to not just fix things, but to get the infrastructure ready for the future."

Campbell and his team, including Network Infrastructure Director Mary Wymbs, couldn't see into the future, but the growing supply of smartphones, tablets and notebooks students and faculty were bringing to campus made one thing clear: Rather than investing scarce dollars in a big wired infrastructure and computers that sat on desks, they decided to encourage users to bring their own devices to campus and focus IT resources on providing the wireless access, security and virtual applications they required to do their work.

In fall 2012, RCCC formalized its BYOD plan by requiring students in its nursing program to bring their own devices. Since most students already had their own notebooks or qualified for them through Pell grants, the RCCC officials received no pushback. But as IT leaders at colleges around the country are realizing, the shift to a full-blown BYOD campus requires a lot more than just welcoming outside devices.

What differentiates BYOD in higher education from other settings is that IT departments aren't only dealing with staff. They're also figuring out how to securely deliver content, applications and services to student devices, which are more difficult to manage, according to Marti Harris, research director for Gartner's Higher Education Strategies group.

The advantages are worth it, however, Harris says. Instead of viewing BYOD as an obstacle, institutions should look at user devices as opportunities to offer new channels for providing community information — such as campus maps, parking lot capacity updates and administrative services — and delivering applications to enhance teaching and learning.

"It is different than just logging in and accessing something," Harris says.

Cecil College CIO Stephen diFilipo knows a lot about BYOD. He spent months researching the topic for a report for EDUCAUSE, which he co-authored in March. Ask him about the trend, and he sets the record straight: BYOD is nothing new. Students have been bringing their own devices to campuses for decades.

"What is new is the proliferation of these devices. They're everywhere," diFilipo says. "Now everybody has two or three or four things they're bringing."

He illustrated that point at a prior job, when he stepped outside with the college's president and motioned to the students milling about. "These kids aren't lighting up cigarettes," diFilipo pointed out. "They're lighting up their phones. So what do we do with that?"

The answer, he says, is investing in middleware. Investment in cellular and Wi-Fi coverage, network architecture and web-based access to services and data all supports mobile.

To Go Mobile, Think Wireless First

Step one at Cecil College meant ensuring cellular coverage on campus was strong. Sprint and AT&T already had towers nearby, but Verizon's coverage was spotty, so diFilipo contacted the company, which came out and added repeater antennas throughout campus.

"Now our students know they've got really strong cellular service on campus," diFilipo says. "That's also valuable in an emergency."

Before moving to BYOD, RCCC performed a wireless survey and, based on the findings, upgraded its entire wireless network across all seven of its campuses. Wymbs and her team used Cisco Nexus for server distribution and HP access and distribution layer switching. They added access points, LAN controllers and an intrusion prevention system. They built in network redundancy and installed management devices to detect problems or raise red flags.

"It used to be the first sign we had of a problem was a phone call from a user," Campbell says. "Now we're actually addressing it, and in some cases notifying people that there may be a problem, or we're able to head it off entirely."

Making Everything Device Agnostic

As campuses shore up their wireless networks, the next step for many is to move services, from the learning management system to course registration and financial aid forms, to device applications or web-based browsers.

Not all campuses have that luxury because they're tied to legacy systems, diFilipo says. Cecil College has "been building away from those and pushing everything to the cloud."

Percentage of U.S. undergraduates who own smartphones. The number of students who say they use the devices for academic purposes nearly doubled from 2011 to 2012.

SOURCE:"The Consumerization of Technology and the Bring-Your-Own-Everything (BYOE) Era of Higher Education" (EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research, March 2013)

At RCCC, Campbell plans to get the school's 3,000 devices down to about 1,000 (primarily in faculty offices and labs), and focus on virtualizing applications and delivering educational content as a service.

"That's a much better use of our resources than owning computers," he says. The college now has a limited Citrix deployment and plans to roll it out on a broader scale in the fall. "That's going to take this to the next level for us. We'll be able to deliver Microsoft Office to a tablet."

His team also plans to build active directory groups for classes so that when students log in to their user accounts, they'll be able to access all of the applications required for their classes. As higher ed institutions build out infrastructure to prepare for BYOD, they must simultaneously let go of it. Gone are the days of mainframes, when IT departments were in control and could dictate which devices, operating systems and software were allowed.

"In IT, we can't just say no," says Kevin Bubb, CIO at Michigan's Lansing Community College.

LCC students are bringing in multiple devices for educational purposes, as students are throughout the country. Rather than try to limit them, Bubb and his team instead monitor the access points on campus. If and when they find areas that are saturated, they increase bandwidth.

What Else Is There?

Colleges and universities need to be prepared to do more than simply meet the demand from today's devices, Gartner's Harris says. During a recent meeting with higher ed CIOs, one mentioned the burgeoning "be-your-own-device" trend toward wearable technology.

"The technology is changing so quickly," Harris says, and institutions must be flexible as they consider BYOD.

"Accept that stuff is going to come at you at a vicious rate that you can't get your head around," Cecil's diFilipo says, adding that he's currently testing Google Glass. "Manage the access, not the assets."

Much of the data on campus is protected by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act or other federal regulations, so IT must ensure that users are limited in what they can access on the network.

Institutions also need to secure their wireless networks to protect them from viruses on user-owned devices, Wymbs adds. Her team segmented RCCC's wireless network and integrated the college's user logins with students' and faculty's personal devices so they could access resources without getting into areas on the network where they shouldn't go.

"We didn't want to lock it down so tightly that they couldn't access the resources they needed. It's a fine balance you want to strike," Campbell says.

Security is more difficult with BYOD, "because you're trusting devices that you can't manage," Wymbs says, "but you can build the infrastructure to protect yourself."

Cecil College identifies sensitive data on campus and encrypts it in transit via Secure Sockets Layer. It also uses roles and permissions to manage who can access that information. "We're not worried about them getting somewhere they shouldn't be," diFilipo says. "If we build the systems properly, they can't get there. It's a different philosophy than 'We must lock everything down.' "

Sign on the Dotted Line

Users at Cecil College who connect personal devices to the college's email system must sign a document stating that they will keep screen locks on their devices, use device-tracking software and notify the college immediately if and when a device is lost so that IT can wipe it clean.

diFilipo's team also is working on a system to track devices that connect to the college's backbone — for instance, student and faculty devices that connect to classroom projectors — and to register and secure users while they're connected.

Lansing Community College is "in the baby steps of this," Bubb says, but also is looking into requiring employees to sign documents stating that anti-virus software will be kept on their devices and is granting permission for remote wipes when devices are lost or stolen. LCC also is considering application containerization, which allows users to keep personal and college-related applications separate. In cases of emergency, sensitive information can be wiped without affecting users' personal data.

"We're trying to work together to find a solution that accommodates our users but also keeps things secure," Bubb says. "It's a balancing act."