A Closer Look at Mobile App Development for Colleges

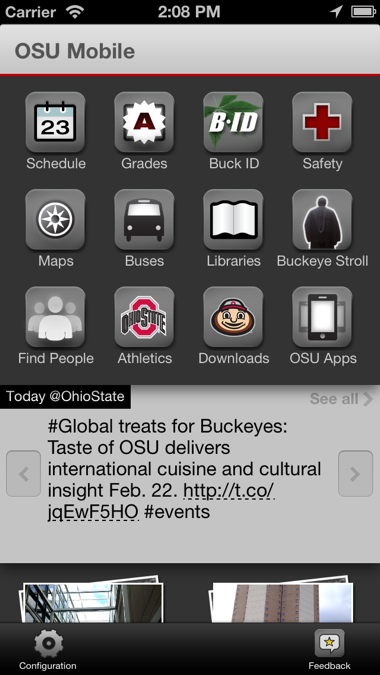

Credit: The Ohio State University, Office of the CIO

In the fall of 2010, an Ohio State University student told Steve Fischer, web and mobile apps director, that “OSU is a an awesome school, but we don’t have a mobile app.”

When student focus groups voiced similar sentiments and his undergraduate assistants began to play with mobile development, Fischer harnessed their energy. As a result, OSU Mobile for iOS was born in July 2011; an Android version followed in October 2011.

At the University of Michigan, an app arose out of the March 2010 purchase of the student-developed iWolverine app, says Cassandra Carson, assistant director of enabling technologies. Similarly, education-technology company Blackboard got into the campus app business with its customizable Blackboard Mobile app after it acquired Terriblyclever Design, a company founded by the students who built iStanford, in July 2009, says Emily Wilson, director of Blackboard’s mobile product marketing.

With student appetites for mobile apps well established, early adopters can offer some advice to institutions embarking on the development of their own app, or app 2.0.

Keeping Up With The Joneses

The cost of an app lies primarily in its development. Ohio State employs two mobile developers and a part-time designer to keep its app up to date, Fischer says. Other related costs include the associated servers and licenses, although the development tools themselves are often free.

Some institutions choose to outsource the work. Blackboard helps its clients build a branded app that combines 14 out-of-the-box modules with university data streams. According to Wilson, most clients sign three-year contracts.

For apps that enable access to private information, such as grades, secure coding is important. According to Carson, U-M’s security team conducts an ethical hacking test before rolling out new features. To further enhance security in the mobile space, students are encouraged to lock their devices.

At OSU, the use of a single sign-on ensures both security and privacy of data, says Jim Muir, a senior developer at the university. Like U-M’s Carson, Muir stresses that proactive communication between developers and the network security team can prevent issues from arising. OSU’s security team reviewed the code before its app was launched.

Once an app goes live, the greatest challenge is keeping up with the rapidly evolving mobile marketplace. “You’ve got an operating system, a device, a network, a network carrier — all these moving things you have to be thinking about. Stuff changes every 60 to 90 days in this market,” Carson says.

Apps for the Future

25,000

The number of updates downloaded in three days after Ohio State University’s last major iOS app upgrade

Source: Steve Fischer, director of web and mobile apps, Ohio State University

In this rapidly evolving environment, everything from the code base to an app’s features remains open to alteration.

Although both Ohio State and the University of Michigan distribute native apps, the rise of HTML5 and hybrid app development means colleges are forced to review their mobile strategy often. Michigan’s Android app, for example, is built in their web framework, Kuali Mobility Enterprise. The product of a consortium of universities and vendors, Kuali Mobility Enterprise’s goal is to develop apps with a single code base usable over multiple platforms, Carson says. Within a few months, the U-M iOS app also will be shifted to Kuali Mobility.

At the University of Wisconsin, app developers don’t take an HTML5-versus-native-applications approach. Rather, the very popular Mobile UW app “is a mix of both where each works best,” the developers tweeted during an EdTech TweetChat last month.

OSU’s focus has been on creating native apps that communicate more effectively and display more personalized content. Fischer foresees push notifications based on geolocation or time of day, and information feeds tailored to a user and the courses in which he or she is enrolled.

“Page views might go down,” Fischer says, “but effectiveness, usefulness and usage of our app would increase.”

No matter their form, apps aren’t going away. A TeleNav survey indicated that 40 percent of iPhone users would rather give up their toothbrushes than their mobile devices for one week. And according to Wilson, students “want to consume information right away, and they want to consume it via an app.”