McKissack, which uses Promethean interactive whiteboards and mobile technology carts outfitted with Dell Latitude laptops and Office 365, recently showcased its students’ STEAM projects (in science, technology, engineering, art and math) at an education event held at Tennessee State University.

“It’s just good teaching and learning,” Chappelle says. “We’ve found PBL combined with technology to be one of the best ways to engage students in their academics and expose them to different real-world topics.”

The concept of “learning by doing” isn’t entirely new, but it’s come roaring back into vogue in recent years.

“It really is a phenomenon that is accelerating at elementary and secondary schools all around the world,” says Suzie Boss, coauthor with Jane Krauss of Reinventing Project-Based Learning, Third Edition, published by ISTE, the International Society for Technology in Education.

A key reason for PBL’s popularity is that, combined with technology, it provides the real-world relevance needed to fully engage students.

“It allows students to answer that age-old question that they have always asked: Why do I need to know this?” says Krauss. “And that’s because what they’re doing and learning is more like the outside world that they’re going to enter — whether it’s college or career — and how they’ll interact within it, whether it’s problem-solving through collaboration and critical thinking or creating things or having opportunities to learn new technology skills.”

CHECK IT OUT: Here are 5 Steps to a Successful K–12 STEM Program Design

At-Risk Students Gain Practical Skills in Problem-Solving

ACE Leadership High School in Albuquerque, N.M., has a curriculum based solely on technology-enhanced PBL as a way to retain at-risk students.

Tori Stephens-Shauger, ACE Leadership HS Photography by: Photography by Steven St. John.

“It provides the learning relevancy that these older students need to really engage and find their purpose in school,” says Tori Stephens-Shauger, ACE Leadership’s executive director and principal. “They’re not just doing a project at the end of a book unit. We design real tangible problems, real situations for them to explore and solve, and it sets up kind of a pressure system for learning, where kids are now willing to take some academic risks to learn the hard skill or concept that they may have previously struggled with, just so they can have their answer to this project.”

Among other tools, students have access to Chromebooks and Acer laptops, which they use to complete six projects throughout the year.

ACE Leadership is unique in that all PBL is designed to help students develop problem-solving skills common to three industry areas: architecture, construction and engineering.

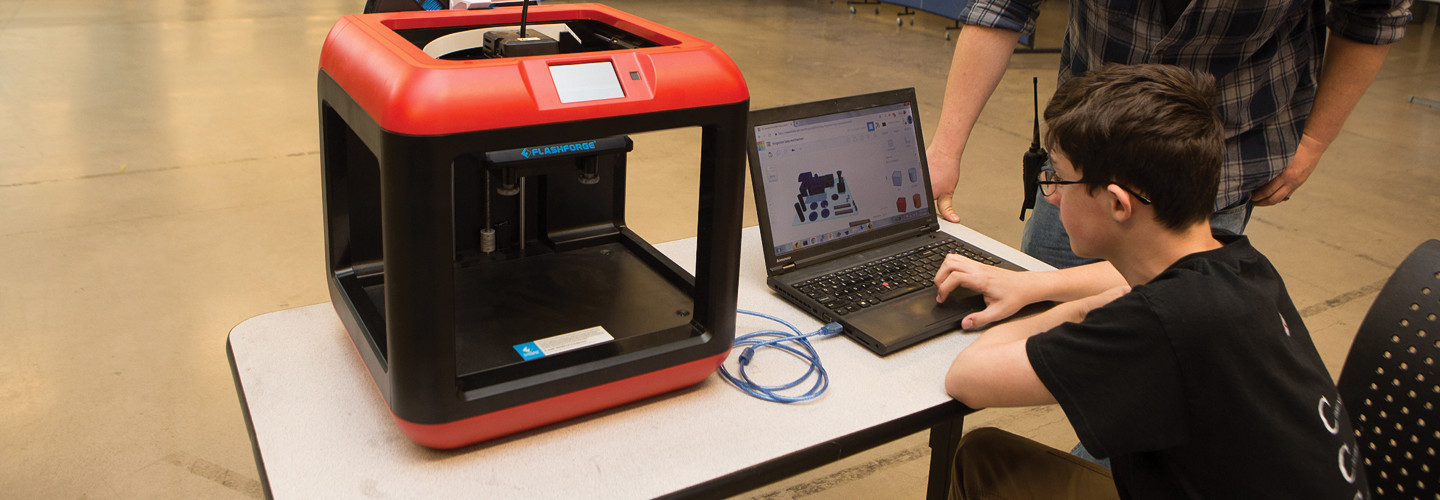

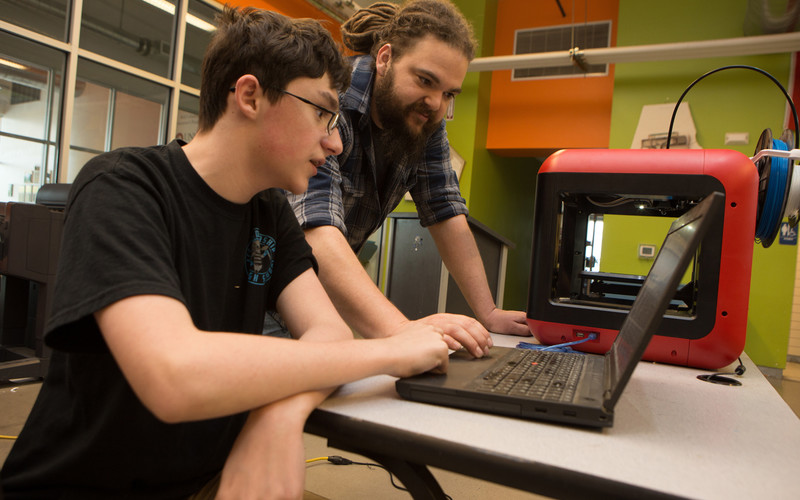

As part of a project highlighting medical innovation, for example, students were tasked with creating a prosthetic hand that included a second opposable thumb. Students used 3D modeling applications such as TinkerCAD, 3D printers and laser cutters to produce their prototypes.