Athletes at Mission Viejo High School in California huddle after their matches, pushing each other to improve. “The kids will say, ‘We need to communicate better, let’s meet to talk about our strategy,’” says Tiffany Bui, the team’s faculty adviser. “They’ll talk about what went well, what didn’t go well. It’s interesting to see the players guide each other. You see leaders emerge.”

Roughly 100 miles north, at Duncan Polytechnical High School in Fresno, officials hope that student-athletes are building skills that transcend sports. “What we really want is for the students to come out of the sport knowing how to collaborate, how to communicate, how to value and respect their team members,” says Fresno Unified School District CTO Kurt Madden.

These athletes chase glory, not on the track or football field, but on video game screens. Responding to the rise in competitive gaming — professional esports tournaments garner millions of online viewers, and some colleges and universities now offer scholarships for top players — school-sanctioned leagues have arrived at the high school level.

In just the past year, the number of schools represented by the High School Esports League (HSEL) has grown from around 200 to more than 1,200.

MORE FROM EDTECH: K–12 schools uncover academic benefits associated with esports programs.

Esports Offers Tangible Benefits Beyond the Field

Proponents say that high school esports programs transform what is often an isolating activity into a social experience, leading to many of the same rewards as traditional athletics. By creating an esports program, Mission Viejo and Duncan high schools hoped to give their student gamers a chance not only to hone their craft but also to learn how to be team players.

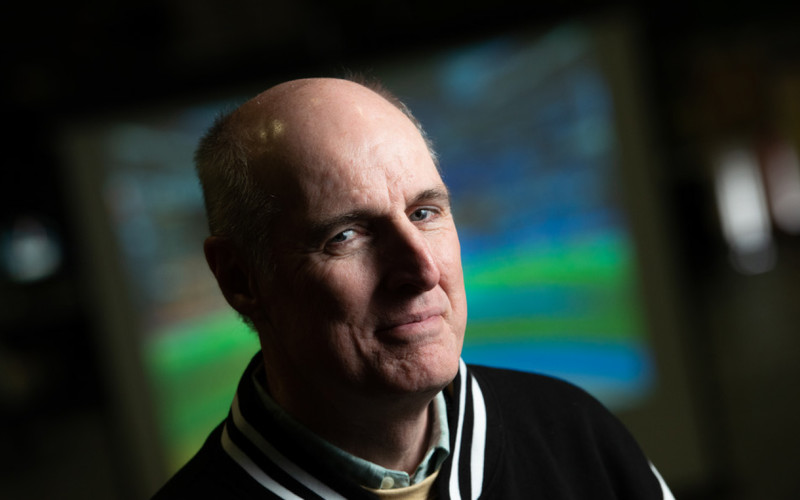

“There’s historically been a stigma associated with gaming,” says Steve Jaworski, head of strategic partnerships for HSEL. “Teenage gamers have been stereotyped as ‘basement dwellers,’ especially when others in their school communities frown on gaming as a waste of time. Now, instead of feeling alone, they’re welcomed into the community. They’re contributing to the school ecosystem, and they’re passionate about being rewarded. These previously disenfranchised young people are being accepted — and, in many cases, celebrated.”

How K–12 Schools Get Their Esports Programs Started

Often, schools can leverage their existing IT investments to support esports programs. At Saddleback Valley Unified School District (home of Mission Viejo High), getting a program off the ground mostly involved purchasing some extra memory and better video cards for existing desktops, as well as making firewall adjustments to allow video games through the district’s content filter. Students in the district compete in the games “Overwatch” and “League of Legends.”

“We did a lot of preplanning,” says Ozzy Cortez, CTO for the district. “It was a group effort to say, here’s this awesome opportunity, here are teachers who are willing to jump into this. And the student response was overwhelming. It was very exciting.”

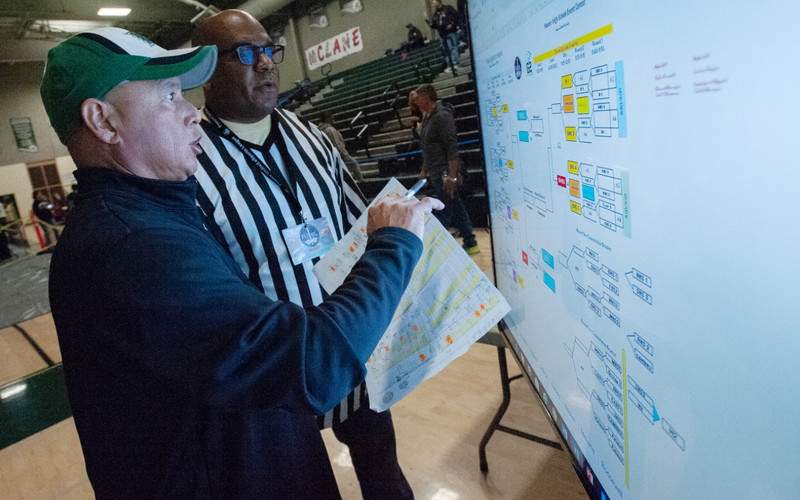

Fresno USD created its own esports tournament, with the district’s 12 high schools squaring off in “Rocket League,” a game that has been described as “soccer, but with rocket-powered cars.” To prepare, students practice with their teams after school and compete against other schools in scrimmages.

Most students, Madden says, play on HP EliteBook 850 notebooks that the district had already purchased, and connect via existing Cisco 802.11ac wireless access points. The district purchased nearly 150 game licenses at around $20 apiece, but some students use their own licenses so they can continue building up their individual player ratings.

The esports program at Oswego East High School in Illinois is in its fourth year, and last year the team won a state championship. The district has whitelisted video games on district computers (after-school hours only), and students play on Dell OptiPlex 7020 desktop computers connected to Ethernet.

“The first year, it was pretty much flying by the seat of my pants,” says Amy Whitlock, a French teacher and gaming enthusiast who serves as the team’s faculty adviser. Over time, the school’s “Overwatch” and “League of Legends” teams have grown to around 35 students, making esports one of the most popular extracurricular activities at Oswego East. “They have jerseys, they bring in their gear — they’re super-serious,” says Whitlock.

Esports in Academics Creates Constructive Student Connections

By bringing gamers out of their bedrooms and into after-school clubs, educators say, they’re able to promote a collaborative environment. “It’s all about creativity and collaboration,” says Ron Pirayoff, director of secondary education for Saddleback Valley USD. “Those are tenets that we’re trying to support every day in all of our subject areas. I look at esports as a vehicle for engaging kids. It’s really been a way for us to reach a different population.”

Fresno USD’s Duncan High doesn’t have traditional sports, but the esports program allows students to represent their school and compete against their peers across the city. “We won our scrimmage against one of the biggest schools in Fresno, and our students were just on fire,” says Uvaldo Garcia, a history teacher at the school and the esports club adviser.

Garcia says the club helps build social skills, especially for kids who feel left out. “This is a good place for students who won’t fit in on a lacrosse or football team,” he says. “I’m excited to have students who maybe wouldn’t fit in anywhere else, and they come here and find what they’re looking for. I was never the athletic type myself. For me, it just seems natural to have students come in and do what they love doing.”

“I think it did provide a way for students who normally aren’t involved to be proud of what they’re contributing,” says Whitlock. “We’ve had a lot of success. They like to win, and they like to be acknowledged for the trophies that they’ve brought to the school.”

Heather Niessner, a technology specialist for Oswego Community Unit School District 308, is also the mother of two boys who participated in Oswego East’s esports program. Both teens were varsity soccer athletes, but they chose during their senior year to skip the pitch in favor of esports. Niessner says their experiences on the playing field and in the computer lab had more in common than people might think.

“They took some of those skills from soccer and applied them, figuring out what they were going to do to defeat those opponents,” Niessner says. “They did more analyzing of video footage, strategy and things like that with esports than they did with soccer. It was definitely a team sport.”

MORE FROM EDTECH: Unconventional classroom design helps foster collaborative environments.

How Administrators Can Encourage Educators to Buy Into Esports

It’s no great task to get teenagers excited about gaming. Garcia’s students greeted the esports program with cries of “Finally!” And Bui says her students are constantly telling her how cool it is that they’re playing video games at school. But adults can be a tougher sell. It’s not uncommon for esports advisers to receive sideways glances from their colleagues, along with muttered comments about “too much screen time.”

Mason Mullenioux, CEO of HSEL, says educators typically come around once they see students begin to have success. One Kansas district, Mullenioux says, improved student engagement and set a record for attendance after integrating esports into its curriculum. “I can’t tell you how many teachers and parents have written in about students completely turning around, coming out of their shell, smiling and having a good time,” he says.

Bui says she occasionally fields a stray comment about how gaming isn’t a “real sport.” But overall, she says, the esports program at Mission Viejo has largely been well received.

“I expected some pushback, but there was no negativity at all,” Bui says. “When I was in high school, that would not have been fathomable. We’re making progress.”