Data Center Colocation Helps Higher Education IT Control Costs

With the rise of cloud providers and commercial colocation centers, higher education institutions have more choices than ever about where to store and process their data.

This doesn’t make the decision any easier, however. At many colleges and universities, data centers are nearing the end of their useful life, and the question of whether to build a new facility or move operations to a colocation center requires stakeholders to weigh several factors, some of which are in constant flux.

“The challenge is that it’s really hard to come up with any sort of comparison, because organizations often don’t even know how much they’re spending right now,” says Jennifer Cooke, research director for data center trends and strategies at IDC.

Some institutions, after conducting intensive cost-benefit analyses, decide that building new is the best option. Others make the switch to colocation, and still other institutions invite outside organizations to share space in their on-campus data centers.

Colocate with a Public Partner

The Ohio State University’s data center sat in a 54-year-old building that was never designed to house IT resources. When a university risk management committee compiled a list of all the risks facing the institution, the out-of-date data center and lack of offsite backup ranked near the top. To better understand the options for addressing those issues, Ohio State engaged an outside consultant.

“They came back and said, ‘To stay where you are, you have about $4 million in deferred maintenance,’ ” recalls Bob Corbin, senior director of infrastructure. “That was just to keep the lights on.”

Building a new facility, on the other hand, would cost around $40 million. The third option was outsourcing.

Ohio State reached out to commercial colocation facilities in central Ohio for pricing and availability, but also began conversations with the state government, which operates a large data center near the edge of the university’s campus.

“We quickly realized that they could support us from a power, space, security and pricing standpoint,” Corbin says. “And they were willing to partner with us, to make sure we were comfortable with physical security, cameras, access controls on the building and redundant power systems into our section.”

The university finished moving its infrastructure to the state facility in July 2015 and has razed its old data center. The move enabled the university to eliminate five full-time positions and to cut annual data center expenses in half, from $2 million to $1 million.

Yet the move required a shift in culture, Corbin says: “We have positions that will no longer be needed. If your office today is in that data center, and you’re the server person, tomorrow your office is not going to be in that data center. You need to start architecting systems that you don’t need to walk in and look at every single day.”

He emphasizes that preparation was paramount. “Anytime you move a data center, it’s all about planning and it’s all about communication. You can’t overcommunicate what you’re moving, when you’re moving it and the impact on users, if any.”

Still, Corbin says, there was virtually no impact on users, in part because the project team spent six months to plan and create an inventory of every single system in the old data center. “We moved every system without any unscheduled downtime,” he says.

Build to Suit Your University's Needs

When a bad windstorm in 2009 knocked out power at many of the University of Dayton’s facilities, CIO Thomas Skill took that as a sign.

“I said, ‘We may have an ‘in’ with God, because the only thing that didn’t go down was our data center,’ ” says Skill, who also serves as the university’s associate provost. The data center lacked generator backup, and the university’s data could have been corrupted in the event of an outage.

“I said that this was God’s last warning: Either we fix it ourselves, or he’s going to let it break.”

However, when Skill suggested that the institution build a new data center, the Board of Trustees was opposed to the idea, preferring that Skill first explore colocation. He conducted a thorough analysis to compare the cost of the two options, and it turned out that the five-year cost of colocation was actually $1.3 million more than converting space in an on-campus building into a modern data center.

Skill notes that, if the institution were making the decision today, “we might have a different conversation.” Since 2009, cloud options have grown, more colocation centers have sprouted up, and the university has more ready access to high-capacity connectivity.

Still, the on-premises data center is expected to last for 15 to 20 years, Skill says, and leaves room for the university to grow its systems or lease out space to other organizations. Staying on campus has also meant that the university didn’t have to worry about running out of space in a colocation center (or, conversely, overprovisioning resources).

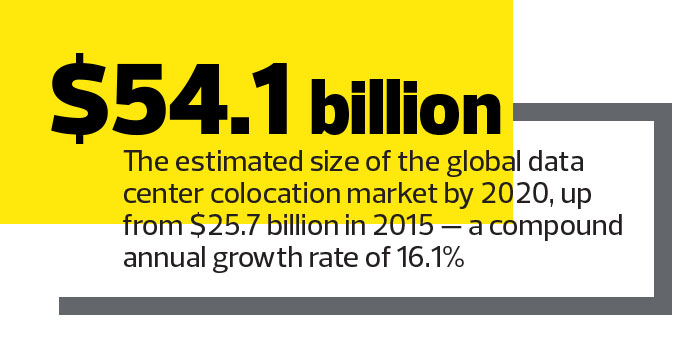

SOURCE: Markets and Markets, "Data Center Colocation Market"

Host a Public Partner

As part of a new IT Center dedicated in late 2013, the University of Hawaii constructed a disaster-hardened, 8,000-square-foot data center. Meanwhile, the state of Hawaii has been moving its data center infrastructure to colocation environments, and it turned to the university to host its disaster recovery capabilities.

“Having just constructed a new data center facility, we did have some space that we could make available to the executive branch to provide them with an alternative site that’s separate from their commercial colocation facility,” says Garret Yoshimi, vice president for IT and CIO for the UH system. “We were interested in sharing with our state counterparts, both to give them a good alternative site and to help them save some money."

Although the agreement with the state helps UH make the most of its data center, Yoshimi doesn’t foresee a situation in which moving resources to the cloud will leave the institution scrambling to fill empty space.

“Some of our large peers are cloud-first,” Yoshimi says. “From our perspective, based on our geographic location, our approach to the cloud is really on a case-by-case basis.”

“If I were to predict out,” he adds, “I would say we’ll be not necessarily full, but we’ll have a hefty load in our data center.”