Personalizing Online Classes: The Potential of AI

The impact of COVID-19 on AI in higher education is hard to predict, says Kathe Pelletier, director of Student Success Community Programs at EDUCAUSE. The economic impact of the pandemic may cut spending in research and development, but institutions could look to AI agents for efficiencies as they operate with fewer staff, she says.

The forced move to online teaching did crack some cultural barriers that have slowed adoption of AI tools and the adaptive learning strategies they support, says Pelletier. “Some faculty members who have historically resisted change began to recognize the value of all sorts of technologies during lockdown.”

Enabling adaptive learning, which personalizes learning for individual students, is one of the most promising aspects of AI, she says. Realizing that (and the rest of the technology’s potential) will take time, however.

“AI can process a tremendous amount of data and give students what they need when they need it,” Pelletier says. “It extends the human capacity to access information, to optimize research and make it more efficient. It can also be the basis for more personalized learning pathways. But humans have to develop algorithms for those pathways, and development time is significant.”

MORE FROM EDTECH: Learn how to prepare your IT department for an AI skills gap.

Using AI to Maximize Efficiency, Improve Quality of Classes

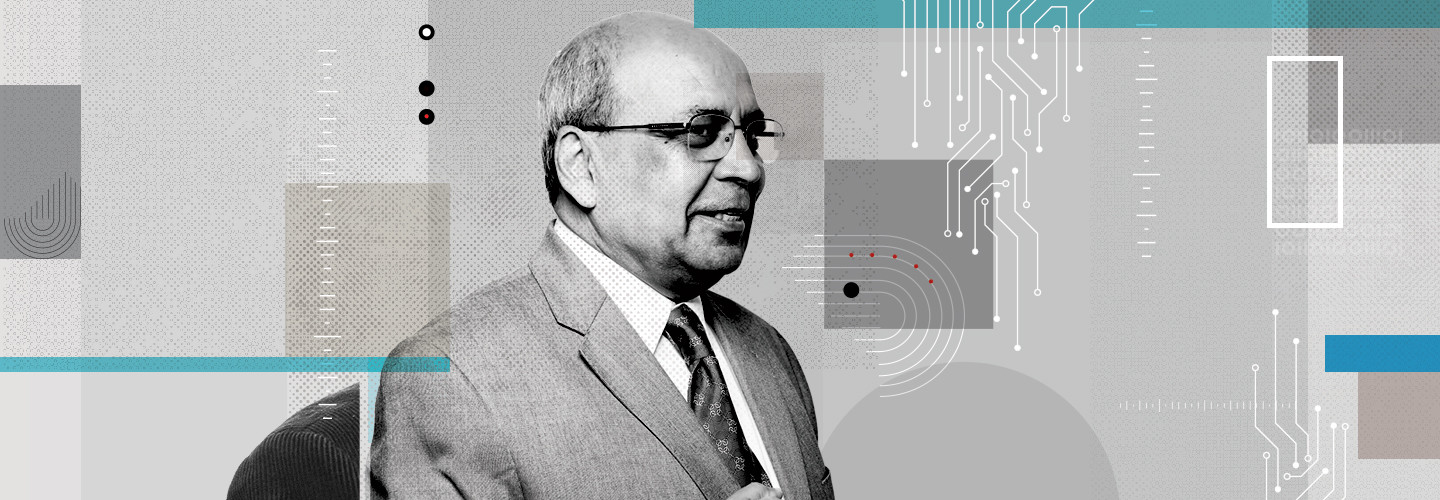

Goel acknowledges the arduous development process that produces AI applications. The original teaching assistant application initially took more than 1,500 hours to program, even using IBM Watson technology. However, a sibling application, dubbed Agent Smith (a nod to The Matrix), can clone a Jill Watson for a specific course with about 10 hours of human input, Goel says.

“We want to use AI to build AI,” he says. “We’re working to take Jill Watson to the Georgia Tech level, where it can be used for any class here. Eventually, we want to share the technology with other universities and with high schools.

Agent Smith means I could go to a busy middle school teacher and offer her the support of a Jill Watson with the investment of just 10 hours of work.”

One variation on Jill Watson can independently read documents and answer questions about, for example, a syllabus or a reference manual. Another, named VERA (Virtual Ecological Research Assistant), enables users to construct conceptual ecological models and run interactive simulations.

Yet another assistant, named SAMI (Social Agent Mediated Interaction), in development, is designed to address a lack of social contact and emotional engagement for online students by alerting them to interests and backgrounds they share with classmates.

“Can AI build better, stronger human interaction? We hope so,” Goel says. “But the application also raises questions of data privacy and security, bias and trust, which we’ll have to answer as we continue with AI.”

MORE FROM EDTECH: Learn how emotionally intelligent AI advances personalization on campus.

A Better Way to Learn a Foreign Language

Students of Chinese language at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) can be encircled by a panoramic screen and find themselves surrounded by human-sized images in what could be a Beijing marketplace. One student’s unscripted negotiation with a vendor might be interrupted by another shopkeeper negotiating the price. Both merchants are AI agents developed as part of the Mandarin Project.

RPI was the first university in the U.S. given access to IBM’s Watson AI technology, which led to the creation of the Mandarin Project in 2012. From there, RPI and IBM established the Cognitive and Immersive Systems Lab (CISL) to explore the use of AI to stimulate “embodied learning,” says CISL Associate Director Jonas Braasch.

“We want students to learn how to translate what they’ve learned from textbooks into the real world,” he says. “Because AI has a long history in gaming, we use similar techniques like interactive engagement with synthetic characters, along with the aspect of rewarding success, rather than marking off for mistakes.”

At present, the Mandarin Project and CISL are only available onsite, but COVID-19 has prompted researchers to explore adapting the technology for different delivery modes.

At CISL, the use of AI in higher education aims to support human instructors, not replace them with bots, Braasch says. “Our systems can increase engagement, and that increases learning. AI can increase the fun of learning.”

MORE FROM EDTECH: Here are 3 ways that AI can improve campus cybersecurity.

Smart Facilities: How Artificial Intelligence Reduces Costs

AI-based technologies are taking a central role in building operations at the University of Iowa. Leveraging IoT data from sensors embedded in heating, cooling, electrical and security systems, the university relies on AI to manage energy use, maintenance expenses and user comfort in 70 percent of its academic buildings, says Don Guckert, who retired in July as Iowa’s associate vice president for facilities management.

“We’re taking advantage of what’s already in place with our building and mechanical systems and using artificial intelligence to optimize energy consumption and maintenance costs, reduce risk to business continuity and increase the comfort of our buildings,” Guckert says.

In the past three years, the university has expanded a fault detection and diagnostics project to cover more than 55 buildings. The initial investment paid for itself through reduced energy and maintenance costs in approximately a year, Guckert says.

When Iowa shut down its campus in March and moved to online classes, some staff remained. Should one of them test positive for COVID-19, access card data can trace the person’s movements, thus simplifying contact tracing and identifying areas for decontamination, Guckert says.

Using AI, he continues, is an effort to move beyond the traditional reactive maintenance model. “As an industry, facilities management has always been complaint-based. We wanted to use technology to get ahead of problems before they happen.”